This is a Voigtländer Bessamatic Deluxe made by Voigtländer AG Braunschweig between the years of 1962 and 1967. It is a slightly improved model to the original Bessamatic from 1959 with the addition of a T-shaped “Judas window” above the exposure meter which allows both aperture and shutter speed settings to be read from within the viewfinder. It also received an improved, and much easier method for resetting the exposure counter. The Bessamatic competed against other German leaf shutter SLRs like the Zeiss-Ikon Contaflex and Kodak Retina Reflex and compared to those models is said to be more reliable and easier to use. The camera used the same F. Deckel “DKL” mount as the Kodak Retina Reflex, but a slight variation in the lens coupling means the lenses are not interchangeable between the two systems.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/2.8 Voigtländer Color-Skopar coated 4-elements

Lens Mount: Voigtländer F. Deckel DKL Mount

Focus: 3.3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism

Shutter: Synchro Compur MXV Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled Selenium Cell w/ viewfinder match needle, f/stop, and shutter speed readouts

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe and M and X Flash Sync

Weight: 802 grams (body only), 938 grams (w/ lens)

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/voigtlander_pdf/bessamatic_w-finder.pdf

Guide: http://www.cameramanuals.org/voigtlander_pdf/voigtlander_bessamatic_guide.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Voigtländer Bessamatic Deluxe is an outstanding camera in appearance, design, and performance. This camera is fun and easy to use, and produces some of the best images I’ve ever shot using a 35mm SLR. It uses a Synchro-Compur leaf shutter and the F. Deckel DKL lens mount allowing for full flash synchronization at all speeds, and a selection of available lenses including the Voigtländer-Zoomar lens. The viewfinder on the Bessamatic is extraordinarily bright and has a match needle exposure system which makes getting correct exposure a snap. Leaf shutter SLRs don’t always have the best reputation for reliability these days, but when found in working condition, the Bessamatic Deluxe is an absolute joy to use and has quickly become one of my favorite cameras in my entire collection. I cannot recommend this camera enough. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | +1 for overall excellence, the complete package | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.2 | ||||||

History

The photography industry saw a huge change in the 1950s with the rise of the Japanese camera industry and professional photographer’s growing shift from rangefinders to single lens reflex cameras. Although SLRs had existed prior to the 1950s, they were generally regarded as impractical curiosities to most photographers. The Ihagee Exakta was a well built camera that had it’s niche, but it’s awkward controls, dim viewfinder, lack of an instant return mirror, and limited lens mount kept it from widespread popularity with the pros.

Although the Japanese made their fair share of rangefinder cameras too, this was a market that the Germans dominated before and after the war. Cameras like the Leica II/III and Zeiss Contax series were well established platforms that offered superior control and dependability, and many Japanese companies like Nippon Kogaku (Nikon) and Canon released their own interpretations of German rangefinders.

Sensing a need to expand into a new market and establish themselves with their own designs, in 1952, the Japanese company Asahi Optical Company released the first Japanese built SLR called the Asahiflex. Inspired by the KW Praktiflex, the Asahiflex lacked modern conveniences like a pentaprism viewfinder, instant return mirror, and automatic diaphragms, but it was a step in a new direction.

The Japanese were never slow to improve their designs and within a few short years, the Asahiflex evolved into what became the hugely successful Pentax Spotmatic series. Other Japanese companies like Orion and Tokyo Kogaku would release their Miranda and Topcon SLRs with many improved features which helped make them more appealing to the general photographer. By the end of the 1950s, nearly every Japanese manufacturer had a 35mm SLR.

In just a few short years, the Germans found themselves having to play catch up to the excellent designs that the Japanese were churning out on a regular basis. Not wanting to completely abandon the successful rangefinder designs of the past or lose support from companies like F. Deckel or Gauthier who had long been supplying them with leaf shutters, many German companies like Kodak AG, Zeiss-Ikon, and AGFA decided to incorporate familiar leaf shutters into existing rangefinder bodies and create SLR cameras with leaf shutters.

The formula made a lot of financial sense. Why start over from scratch with an entirely new camera and shutter design just to keep up with the Japanese? After all, the Germans were known for making world class leaf shutter rangefinders, so why risk changing that? Plus, using a leaf shutter in an SLR was better for flash photography as the shutter would always be flash synchronized at all speeds, as opposed to the relatively slow 1/30 – 1/60th of a second speeds from Japanese focal plane shutters.

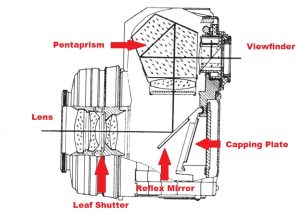

From a technical standpoint, adding a reflex mirror and pentaprism to an existing leaf shutter rangefinder isn’t quite so simple as a number of technical hurdles need to be overcome. Since an SLR requires light to pass through the lens, hit the mirror, and then travel through the viewfinder so the photographer can compose an image, you need to find a way to keep that leaf shutter and the lens iris wide open during composition. But if the shutter is open, how do you prevent the film from being unintentionally exposed? Therein lies the problem.

All leaf shutter SLRs require a complex dance of mechanical movements where the shutter remains open while the reflex mirror is down. A metal door, sometimes called a capping plate, exists behind the mirror and blocks light from exposing the film. The design of the capping plate varied by manufacturer, with some of them being an entirely separate plate and others being part of the reflex mirror assembly.

The drawing to the right comes from Frank Mechelhoff’s page “West German Cameras: How They Lost to the Japanese”. His drawing is of a Zeiss-Ikon Contaflex which is a leaf shutter camera similar to the Voigtländer Bessamatic. I drew red arrows to indicate the key parts of the diagram to help illustrate the complexity of the design.

When it is time to make an exposure, the camera must first close the shutter and stop down the iris to whatever f/stop you have selected. Next, the reflex mirror and capping plate must move out of the way to allow for light to pass through the mirror box and expose the film. With everything ready to go, the shutter is now ready to open and close at whatever speed it is set to. All of this happens quickly in the moment after pressing the shutter release, however there is still a delay of about 1/50th of a second for all of these motions to complete, which could cause problems for fast motion shots where a precise exposure must be made. After the exposure is made, leaf shutter SLRs like the Bessamatic keep the shutter closed and the mirror up, blocking light from entering the viewfinder. You must advance the film to reopen the shutter, and lower the mirror, allowing you to see through the viewfinder again.

The following table summarizes the events that must unfold each time a photograph is taken with a leaf shutter SLR like the Bessamatic.

The following table summarizes the events that must unfold each time a photograph is taken with a leaf shutter SLR like the Bessamatic.

If this sounds like an overly complicated way to make an SLR, you’re right. While overall it did work, the chances for failure were higher for leaf shutter SLRs compared to focal plane SLRs due to the shutter cycling twice for every exposure taken and with the extra moving parts, there were more opportunities for things to go wrong.

Despite this complexity, many German camera makers made their own models. Zeiss-Ikon with the Contaflex in 1953, the Kodak Retina Reflex in 1957, and the AGFAflex in 1958 all had success before Voigtländer would release the first Bessamatic. Being the last to debut their model gave Voigtländer the advantage of being able to see what worked well with it’s competitor’s cameras, and make adjustments accordingly.

I mentioned in my review for the Voigtländer Prominent that Voigtländer was an eccentric company that made quality products their own way, eschewing the norms established by others. And while this applies to many of the company’s models, the Bessamatic is somewhat of an exception. Unlike many of the company’s other models, the ergonomics of the Bessamatic were quite good. Most of the camera’s key controls were in logical locations where you’d expect to see them. Focus was changed on the lens, there was a rapid wind advance lever, the viewfinder had both a microprism and split image focus aide. The camera had an elegant symmetry to it’s design, and had a very shiny and smooth chrome plating. Everything about the camera exuded Germany quality without most of the German eccentricities that other German SLRs had.

The lens mount on the Bessamatic is called the DKL mount which was a type of interchangeable bayonet lens mount designed for F. Deckel Compur shutters. Several companies used a variation of the DKL mount including Braun, Balda, Iloca, and Wirgin. But the two most well known companies to offer models with the DKL mount were Kodak and Voigtländer.

The greatest appeal to the DKL mount is that the lenses often could be swapped between rangefinders and SLRs made by the same company, but oddly, many DKL mount lenses couldn’t be swapped between models by different companies. Lenses produced for the Kodak Retina IIIS or Reflex models could not be used on Voigtländer models, and vice versa. The only difference is the location of a notch on the lens mount which prevents lenses from one company being used on another model. In the image to the right, I show the DKL mounts for a Kodak Retina Reflex IV and the Bessamatic. Notice the notches indicated by the yellow arrows on the Kodak are not present on the Voigtländer. Likewise, the notches indicated by the red arrows are not present on the Kodak.

If you really wanted to swap lenses between cameras, you’d either need to modify the lens mount on either camera to remove the protrusion, or modify the lens to add the notch. Rick Oleson has detailed how to do this correctly so that each lens can be swapped between Voigtländer and Kodak models.

Using the Bessamatic’s DKL mount, there were a limited number of options for anyone wanting different focal lengths, and all lenses were made by Voigtländer, making them quite expensive. Most are found today with either the 50/2.8 Color-Skopar or the 50/2 Septon lens. At the very least, all of the common lengths from 35mm to 135mm that rangefinder customers would have been used to were covered plus one more.

That ‘one more’ was the Voigtländer-Zoomar lens, featuring a modest 36-82mm focal length and a moderately fast f/2.8 aperture, the 14-element Zoomar was first designed in the late 1940s by an optical engineer named Dr. Frank G. Back for American television cameras. Although “zoom” lenses existed prior, the Zoomar was the first commercially successful zoom lens and first available in a still 35mm camera. Manufacture of the Voigtländer-Zoomars was done by famed lens maker Heinz Kilfitt in Munich where it was built using the DKL mount, but it was also available in Exakta and M42 mounts. When equipped with the Bessamatic mount, the Zoomar cost a hefty $298 by itself, more than doubling the price of the camera!

The Bessamatic received positive praise in the press and sold well, staying in production until 1967. The article below comes from the April/May 1966 issue of Camera 35 magazine and declares the Bessamatic “a good value for the man who wants a moderate degree of versatility, simple operation plus extremely rugged construction.”

The Bessamatic would receive one update in 1962, which would be unofficially called the Bessamatic Deluxe. The Deluxe model would feature two changes. The most obvious was a T-shaped “Judas window” directly above the exposure meter which allows the shutter speed and aperture values selected on the lens to be seen from within the viewfinder. The other change was the addition of a dedicated knob that was used to reset the exposure counter, simplifying the method to how this was done on the earlier model.

Selling in February 1963 with the f/2.8 Color-Skopar lens for $229.50 or with the f/2 Septon for $299.50, the camera was not cheap. Each of those prices compare to $1900 and $2500 today. putting them in the semi-pro price range of cameras today.

Along with the Bessamatic, there was a meterless variant called the Bessamatic M, which had all of the same features, sans meter. There was also a step-up model called the Ultramatic and the later Ultramatic CS, which both offered Automatic Exposure. The later CS model employed a TTL CdS meter, but was otherwise the same.

Although leaf shutter SLRs were preferred by German companies, Japanese companies like Kowa also released a successful line of leaf shutter SLRs, and even the Soviets got into the game with their Bessamatic inspired Zenit 4-6 models.

As neat as they were, leaf shutter SLRs had a significantly higher number of moving parts than focal plane shutters, and a combination of cost to manufacture and difficulty to repair caused them to fall out of popularity by the mid 60s. By the end of the 1960s, cheaper and more reliable focal plane shutter SLRs were coming out of Japan on an almost daily basis, putting the nail in the coffin for the leaf shutter SLR.

Today, the Bessamatic remains one of the highlights of this design of camera. The Zeiss-Ikon Contaflex and Kodak Retina series sold well too, but the Bessamatic regularly receives praise from modern day collectors due to the camera’s design and reliability. A combination of excellent optics, excellent design, and better than average reliability means that these cameras can often sell for quite a bit of money on the used market, especially when equipped with the less common lenses like the Septon or Zoomar lenses.

My Thoughts

Voigtländer makes some of my favorite cameras. I’ve had great luck with the Vito II, the Brillant, and even a basic folding camera from the 1920s so when I first saw a Bessamatic, it was upgraded to “must have” status. Of course, finding one in working condition at a price I could afford was a challenge.

For those GAS-afflicted collectors such as myself, being patient can be difficult, but it is often rewarding as my patience paid off when I scored this perfectly working Bessamatic in it’s original case for a great deal. When it arrived, it was in better condition that I could ever hope. This thing was mint. Seriously, if I ever were to move to Japan and open an eBay store and sell this camera, I would describe it’s condition as TOP MINT EXC LQQK!!!!!!++++++

The Bessamatic was everything I had hoped for. Where the Retina Reflex has idiotic controls and the Zeiss Contaflex almost never works, this Bessamatic was a gem of German engineering with a crazy bright viewfinder (more on that later), mostly perfect ergonomics (again, more on that later), and one of the shiniest finishes I’ve ever seen on a camera. In fact, the shiny finish proved to be a challenge when photographing the beauty pics I took for this article as I had huge variances in blown highlights in the reflections and darkness in the shadow area. I always prefer taking my beauty pics outdoors, but this is a case where a light box would have been ideal.

Another immediate characteristic to note about the Bessamatic Deluxe is how heavy it is! While German rangefinders and leaf shutter SLRs have never been known to be dainty, lightweight devices, the Bessmatic is one stout camera. Weighing in at 938 grams (just over 2 lbs), this camera is heavier than quite a many other SLRs of the era even with the smallish f/2.8 Color-Skopar. I imagine that most of the other lenses like the f/2 Septon, the 135mm f/4 Super-Dynarex, or the monster Zoomar would have made this thing and absolute tank!

The top plate is quite elegant featuring the rewind knob, ASA speed dial, and aperture selector on the left. There are printed numbers from 1.5 to 5 which are filter compensation factors allowing you to still get a correct reading from the selenium meter when using colored filters on the lens. Permanently mounted to the top of the pentaprism is the accessory cold shoe, and to the right is the threaded shutter release button, rewind mode selector, exposure counter reset knob, and rapid film winder.

One of the two changes to the Bessamatic Deluxe from the original model is that little round knob between the advance lever and rewind selector. By twisting this little knob, you can advance or rewind the exposure counter in either direction. This is much more convenient compared to the older way which required you to put the camera into Rewind mode and reset it by repeatedly advancing the lever. The lever on this camera is short and stubby, but still comfortable to use. Unlike many other SLRs of the era however, the advance lever is not of the additive type, which means that you cannot advance the film with several short movements of the lever. You must complete one full 270 degree movement of the lever to properly advance the film. Only going part way leaves the lever partially extended. The rewind lever deactivates the film advance of the camera for rewinding, but when you are done, a single movement of the advance lever resets it.

Although only featuring the 1/4″ tripod socket, the bottom of the camera is nicely detailed with a large strip of the pebbled body covering, and three little feet that help stabilize the camera when set on a flat surface.

The back of the camera reveals the opening for the large and bright viewfinder and the window for the exposure counter. The exposure counter is of the reversing type like the Kodak Retina in that it counts backwards, showing how many exposures remain on the roll of film. Unlike the Retina however, the camera can continue to be used if the counter reaches 0. To the left of the viewfinder window is a circular disc that serves no purpose. Had this been a rangefinder, I might have guessed this was a rangefinder adjustment cover, but it’s not.

The viewfinder on the Bessamatic is gloriously bright. In fact, it’s brighter than every other SLR of the era. Edge to edge brightness shows no vignetting with only the slightest hint of a circular Fresnel pattern. But how is this possible that this leaf shutter camera from the early 1960s managed to do something that wouldn’t be equaled for at least another decade and a half? By cheating, that’s how!

Okay, maybe saying they cheated is unfair, but the reason the viewfinder is so bright is that most of the viewing screen is just clear glass for light to pass through showing a focused image. Although this improves brightness dramatically, it has the negative side effect of not allowing you to “see focus” on most of the screen.

To properly focus the camera you must use either the split image rangefinder aide in the center of the viewing screen or the microprism circle around it. In the image to the left, the light pole is a couple hundred feet ahead of me, yet I have the camera set to minimum focus. Notice how the center of the pole is offset through the center of the split image, and the microprism circle is distorted, yet the rest of the viewing screen looks properly in focus.

The inability to focus using the entire viewing screen might at first seem like a major omission, but in practice it really doesn’t make much of a difference. I think the dramatic improvement in brightness more than makes up for having to always check focus in the center of the viewing screen.

Finally, the last thing you’ll notice in the viewfinder is the “hoop and stick” match needle on the right. When measuring exposure, the needle indicates an arbitrary light level, and you must make a corresponding movement of the hoop so that the needle is visible within the circle. When this happens, you have correct exposure.

Loading film into the camera first required a gentle squeeze of two protruding tabs on the left side of the camera.

This would open the right hinged film compartment. Film loads from left to right onto a notched, non-removable take up spool like most 35mm cameras of the day. This camera predates the use of foam light seals and I found the ones on mine to still be intact, requiring no replacement. On a side note, it appears that this camera was last serviced around 1980 which partially explains why it’s in such good operating condition.

I mentioned earlier that the Bessamatic uses F. Deckel’s DKL mount which was shared by several over companies, but due to a slight change in the bayonet, only lenses designed for the Bessamatic can be used. Swapping lenses is quite easy, requiring only the push of a release catch near the 6 o’clock position of the lens and a counterclockwise twist.

A characteristic shared by other DKL mount lenses is a clever depth of field scale featuring two red markers that change position depending on the selected f/stop on the lens. When a large f/stop is selected, the markers move close together, indicating a narrow depth of field, but when a small f/stop is selected, the markers move farther apart to indicate a larger depth of field. Like many cameras from this era, the Bessamatic employs a coupled LVS (Light Value Scale) which couples the shutter speed and aperture rings together. With this system, only the shutter speeds can be changed on the lens itself, but if you wish to override it and select a different f/stop, you may using the dial around the rewind knob. This aspect of the Bessamatic’s control layout is my least favorite element, and the one thing keeping this camera from being perfect. I understand that this was common practice back then, but I don’t have to like it. At the very least, its still easier to use than the Kodak Retina Reflex’s infuriating knob at the bottom of the lens mount.

The Voigtländer Bessamatic Deluxe is a fantastic camera, and whatever it was that the company was working on in the years after Zeiss and Kodak released their respective cameras, the extra time clearly paid off. Save for the LVS with adjustment dial around the rewind knob, the ergonomics of the camera are outstanding, the viewfinder is outstanding, the look and feel of the camera is outstanding. But how do it’s images look?

My Results

I often talk on this site about what I call “zoo cameras” which is my generic term of a camera that’s easy, reliable, and fast enough to take with you on a family trip to the zoo. Zoo cameras must not be obtrusive and allow for quick and effortless shots to capture those special candid moments that don’t always wait for you to fiddle with a more complex camera. As far as zoo cameras go, the Bessamatic Deluxe is heavy, weighing over 2 pounds with the Color-Skopar lens attached. I secured the camera with the bottom half of it’s ever ready case and a thick neck strap. Despite it’s weight, the camera is more compact than a large bodied SLR like the Nikon F or Minolta SRT, and has excellent balance, helping to disguise it’s weight.

For the Bessamatic’s first roll, I literally took it to the zoo on a summer trip with my family. Instead of reaching for a predictable roll of Fuji 200, I went on a limb and tried a film called 3M Scotch 200 that had expired in the very early 1990s. I didn’t know it at the time, but this 3M film turned out to be some kind of Ferrania emulsion.

Outstanding! The images that the Bessamatic Deluxe produced on the expired 3M Scotch film were better than I could have hoped for. I knew it was a risk using unknown expired color film for the first time in a new camera, but I was rewarded with an entire roll of spectacular snapshots with incredible detail and a color palette that although a bit muted, was very natural.

From a technical standpoint, I have nothing to complain about with the lens. Sharpness is excellent corner to corner, there was no visible vignetting, and there was no other type of chroma aberrations noticeable on inferior lenses. Bokeh shots are not my thing, so I didn’t attempt those, nor did I experiment much with the lens indoors, but the few lower light shots I made all came out great suggesting that the selenium light meter on this camera is working perfectly. It is not often that I get to review a camera that likely is in as good of condition as it was when it was new. Most half century or more old cameras have some type of compromise, but not this one. I hate to brag, but not only did I love the camera, but the fact that it’s in such great physical and operational shape, elevates this camera to one of my favorites in my collection.

Is the camera perfect? No. The Light Value Scale is annoying as it is on most cameras of the era. It’s also quite heavy, but when secured with a good strap and the camera’s case, I had no issue dangling it from my neck in an all day trip to the zoo. But what an experience! The best part about shooting photographs with old cameras is the experience. There’s the saying, “they don’t make ’em like they used to” and that absolutely applies here. Leaf shutter SLRs have a different sound when the shutter fires, using the match needle to get accurate exposure is fun, and the look through that old Fresnel screen viewfinder is unlike anything you can shoot today. And then to know that your images will come out looking as good as any electronic CPU controlled fully automatic film camera from decades later, that’s the cherry on top!

If it’s not obvious by this point in the review, yes, I love the Voigtländer Bessamatic Deluxe. Last week’s review of the Voigtländer Prominent was of a camera that is probably more desirable by collectors, but that doesn’t concern me. I want to use these cameras, and the Bessamatic Deluxe is one that will get regular use from me!

Additional Resources

http://camerapedia.wikia.com/wiki/Bessamatic

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/page_standard.php?id_appareil=11779

http://thecameracollection.blogspot.com/2010/10/voigtlander-bessamatic.html

http://elekm.net/pages/cameras/bessamatic.htm

https://mikeeckman.com/photovintage/vintagecameras/bessamatic/index.html

https://oldcamera.blog/2018/05/26/voigtlander-bessamatic-2/

What a wonderful review of this lovely camera. Thanks for posting.

I picked up a Type II aka de luxe on ebay from one of my trusted sellers in Germany about three years ago. This came with the entry level Lanthar lens but even so, I got it for an excellent price. Upon arrival I was somewhat gobsmacked to find it in virtually mint condition. (I’m older generation, so mint has to mean mint.) Even better was when I discovered that it worked flawlessly. I subsequently sourced the f2.8/50 Skopar X, f3.4/35 Skoparex and f4/135 Super Dynarex, and lastly the f2/50 Septon. This last cost 3x what I paid for the camera! I’ve not bothered with a Zoomar as this is more a case of being for the collector than a user lens. Quality no where matches what you have to pay to get a decent one.

When you get something as good as this in your hands it brings it home how much better built and finished Voigtlanders were than the contemporaneous late Zeiss Contaflexes, as good as these are, or can be today. (I have four, ending with the S.) As an all-round camera and user experience I prefer it to even my Contarex Super. Now that’s saying something.

Regarding lenses, you’ve missed one from your review. the f4/200 Super Dynarex. Surprisingly, WEP even produced a DKL tele converter.

Hi Mike

Just thought you would like to know that the non-functional “button” to the left of the eye piece unscrews to permit access to a screw on the rear of the light meter assembly.

As far as I can ascertain you can make fine adjustments (I assume zero) after removing a threaded plug.

Cheers

Steve

That’s good to know, Steve. Thanks! 🙂

Great review, thanks! I’ve been wondering whether to buy a Bessamatic or not, but your conclusion makes painfully clear what I should do 🙂

A. Barbera, I’m sure that if you can source a nice one in working order, you won’t be disappointed. Be sure to get the second version aka de luxe as this is an improvement on the original. The one you’re looking for is easily identifiable by the Judas window above the meter.

Unfortunately, cosmetic condition can’t be relied on as much with a Bessamatic than other cameras. They were so well finished, and stand up to wear very well, that condition can be misleading at times. However, the good point is that they were an improvement on the Contaflexes and generally hold up better mechanically.

Happy Hunting!

“However, the good point is that they were an improvement on the Contaflexes and generally hold up better mechanically.”

Terry,

This is not, strictly speaking, correct. For clarity, I’m a huge fan of Voigtlaenders in general, and the Bessamatic in particular. A Bessamatic was the first leaf shutter SLR I ever acquired circa 2007 or 2008 and I have a few more since then. They are probably the best designed type to use quickly and easily because they handle so well. But “hold up better mechanically”? No, I don’t think so. Don’t get me wrong: they are beautifully made, indeed. Absolutely, they are high quality. But, if used hard, they will wear mechanically, and one can run into adjustment problems compensating for this. See Mecking’s excellent repair guides for more on this, if desired.

My own suggestion (as should apply to most cameras 50+ years old) is simply to treat them gently, and use them sympathetically. Ie: do not wind them with excessive vigour. Correctly lubricated, and used intelligently, they will last well enough. Use them hard, and roughly, and sooner or later (probably sooner), you’ll jam them up. If for no other reason than the wind lever arc will move out of spec and fail to reset, due to excessive mechanism play.

The various Contaflex cameras (the Tessar types, at least, the ones most worth using) will obviously suffer from the same sorts of age-related shutter maladies as a Bessamatic, Ultramatic or Retina Reflex. (These SLRs all use essentially the same shutter type with common internals, but certain alterations tailored to their installation, so that’s no surprise). Servicing their (basically conventional) Synchro-Compurs will resolve that. But the Contaflex wind system, with its robust durable, gears (Tomosy, for one, praises their quality), and far simpler, less circuitous connection from lever (or knob) to shutter, all make for a mechanism that wears less quickly. The fact that there are less parts to wear in the first place, is not insignificant.

As much as I love using my Bessamatics, and they are, indeed, a joy to use: by coming late to the party, it was a case of the Superb TLR all over again. Just as Voigtlaender foolishly discounted the 6×6 TLR, until Franke & Heidecke started up and made a success out of it (and then had to reinvent the wheel to avoid infringing patents, to develop their own, admittedly superb, Superb, TLR); Zeiss, by being first, were able to do well by patenting a reliable, durable Contaflex mechanism, which kept the complexity inherent in this particular camera configuration to the necessary minimum.

This is why you will find those longitudinal racks and their related parts beneath the lower cover of a Bessamatic, but not a Contaflex. The Zeiss SLRs don’t have them, because they don’t need them! Voigtlaender had to add substantially more components, to produce exactly the same sort of mechanical functionality Zeiss had already locked up with patents using far fewer parts.

Granted, Voigtlaender at their very best seemed to achieve greatness with a combination of superlative optics and, frankly, eccentric, unconventional, camera bodies. The Superb; Prominent; Vitessa; and of course Bessamatic, all bear witness to that. So it is not all bad news, far from it. The result is an admittedly complex, but still wonderful and underrated 35mm SLR.

It’s also important to put my observations above in some perspective. If you can find a tidy, lightly used example of the Bessamatic, have it stripped and lubricated by somebody competent and then, run a few rolls a year through it with care and sympathy, you can anticipate a great deal of enjoyment and reliability. Potentially, excellent images, also. If, on the other hand you need to shoot a few rolls a week, every week: you’d do better, in the long run, by starting with a good Contaflex Super (or Rapid, if you can find one). Providing, of course, that you can live with the limited range of alternative focal lengths from their Pro Tessars.

For myself, having discovered the delight one gets from actually using a Bessamatic many years ago, I was subsequently distracted by the Zeiss competition and set a goal of really exploring those, by seeking out an example of every Tessar version produced. They are outstanding SLRs, and the late unit focus models feature a recomputed 50mm Tessar which is superlative. But recently, my Bessamatics have been getting a lot more attention quite simply because they are so delightful to actually use, whilst producing excellent images.

I suppose the takeaway is, if you obtain a really good example of either maker’s SLR, you are very unlikely to be disappointed; quite the contrary.

Best,

Brett

Brett, I must defer to your greater in-depth experience, I’ve only one example of a Bessamatic de Luxe, a pristine example in every respect, so I count myself lucky. I’ve one each of the late Contaflexes, four in all, and all are functioning mechanically, albeit the meter in one has packed up. And as with my Contarex Super, they can take a film back, but as I don’t use the camera that has the back I often get confused with the interlock when I occasionaly play with it, either the sheath not being withdrawn, or when it is parked on the rear of the back, not being able to remove the back from the camera!

But you’ve hit the nail on the head: we need to be just a little careful when using them today and to not subject them to abuse, especially given how old all these models are now. And the major problem acquiring one today is we won’t know its history, so we could be buying a lemon just waiting to go wrong! I agree with you regarding the Bessamatic v the Contaflex in the hand. There is a wonderful joy of playing with the Bessamatic that is just missing with the Contaflexes. However, if my experience of them was solely limited to my Contaflexes, I would no doubt be just as happy.

Just a thought about the suggestion that

“the chances for failure were higher for leaf shutter SLRs compared to focal plane SLRs due to the shutter cycling twice for every exposure”.

Well, the shutter opens and closes twice for each exposure but there’s only one cycle. It is cocked once and released once. This is no different to the way a large format camera is used – the shutter is cocked, opened for viewing, closed for the film holder to be slid into place (the dark slide being the equivalent of the capping plate), then released – opened and closed for the exposure. Many medium format film SLRs operate in the same way – Hasselblad 500-series, Zenza Bronica ETR, SQ and GS models, Mamiya RB67 and RZ67. Also, modern focal plane-shuttered mirrorless digital system cameras (or digital SLRs operating in mirror-up/direct-view mode) start with the shutter open for viewing, close it briefly while the sensor is pre-charged, then open and close it for the exposure, and finally open it again to resume viewing. So I would say that there’s nothing about using a leaf shutter that’s inherently damaging or wearing or that makes the mechanism more prone to failure.

It is true that the sequence is more complex, and there’s the motion of the capping plate in addition to the mirror to consider – they don’t move together, even though their trajectory is similar. The mirror swings through 45 degrees, but the Bessamatic’s capping plate moves through 90 degrees and the mirror must be fully raised (to light-trap the viewfinder) before the capping plate can begin to open prior to the exposure. Similarly, when winding the film, the capping plate needs to close completely before the mirror can begin to lower. But the Synchro-Compur shutter, itself, is a bought-in module that is inherently very reliable indeed.

Incidentally, my favourite model is the Bessamatic m, which has no built-in light meter and therefore just has simple shutter speed and aperture selection rings, rather than the interlocked, counter-rotating rings associated with the meter-equipped models. The m is a joy to use, either with a separate meter or exposure guesstimation.

Thanks for the additional analysis. I agree that putting a leaf shutter into an SLR doesn’t automatically make it less reliable, but for many of the models, the additional complexity make them more challenging to get repaired, so there’s probably less of them in good working condition these days.

Dear Mike,

another enjoyable review! We seem to be of the same mind on the virtues of the Bessamatic SLR!

The late and much-missed Tony Lockerbie always spoke highly of the Bessamatic, and used one to great effect. I think he prompted me to take a leap of faith and try one, in spite of “received wisdom” of the day that all lens shutter SLRs are mediocre, unreliable designs, not worth wasting time on. (My experience has been virtually the exact opposite).

Ivor Matanle always rated the Bessamatic, too, and he and I usually seemed to have similar feelings about which vintage cameras were worth using, and which were not.

I fell in love with the first one I acquired way back in circa 2007-2008 for 15 quid or so ex-eBay, in those long gone days when fewer people wanted or used vintage cameras. (Sometimes I miss those days.) It had a few problems, including a former owner shoving his or her pinkies into the capping plate and deforming its actuating lever. They got an “A” for effort, in my book, because if fully cocked, the Bessamatic actually has a actual latch which locks the plate securely closed (unlike most other mechanisms in the same class that rely only on spring tension to keep their plate seated). This should render the Bessamatic plate immune from such carelessness: presumably, they must have poked the plate when the mechanism was only partially wound…

By using a somewhat “gynaecological” technique, I was able to reform the actuating lever of that example without completely stripping it. Not ever having looked at a leaf shutter SLR before, I learned a lot of things from working on it, one of which is they’re not always as bad to repair as people suggest. I’ve worked on others more invasively, since.

I know you put a lot of time, and effort, into your reviews, and this is evident in the quality of the finished product. With hundreds of details involved it’s easy for something to sneak through occasionally, so I did just want to mention, that the earlier Bessamatic version does not actually have to be wound and fired until the counter mechanism is at its correct start. If you can find a photo of the inside of one such, you’ll see that in between the wind sprockets, their shaft has a series of longitudinal grooves machined into it. With the wind lock lever released, these grooves provide enough friction that one can slide a finger across the shaft to quickly rotate it, and hence, the counter, back to the desired setting (depending on the number of frames one is loading of course).

It’s an unusual (and possibly unique) method of counter reset, isn’t it?

Thanks so much for another very enjoyable article. Keep up the good work!

Best,

Brett

Brett, thanks for the feedback and the clarification on resetting the exposure counter. You’re right, with an output of at least one review a week, I do my best to get as much right as I can, but finding that right balance of spending countless hours with a particular model, to ensure I get 100% right, while also not taking months and months in between reviews, some stuff slips through the cracks. I don’t have my Bessamatic in front of me at the moment, but I’ll check mine and update the review accordingly when I find it.

I am quite fond of the Contaflexes and even have a few more in my collection since my original review, but truth be told, I still prefer the Bessamatic, just a little bit more!

As for the rest of the great info you shared, like Terry said, I agree that using these things with care is definitely a requirement. I’d even argue that it was a requirement back then because even though it’s true things were built to last back then, people also took better care of stuff and weren’t as hard on them as things like smartphone where people know every 2 years you can get a new one! 🙂