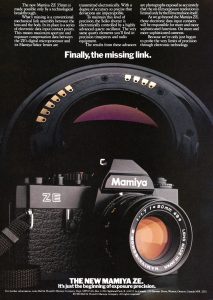

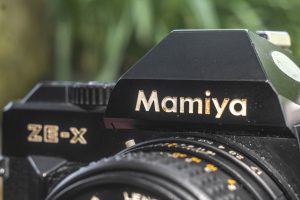

This is a Mamiya ZE-X, a 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera made by Mamiya Optical Co., Ltd. of Japan starting in 1981. The ZE-X was Mamiya’s most advanced 35mm SLR and came standard with a huge number of advanced electronic features, most notably an error-proof type of Auto Exposure which they called “Crossover” in which the camera would still be able to make accurately exposed photos, even if the photographer made a bad choice. The ZE-X used Mamiya’s then new ZE Bayonet which was short lived, but had a good number of lenses available for it. While the ZE-X was chock full of technology and was favorably viewed in contemporary reviews, Mamiya was unable to make a meaningful dent in the competition from other Japanese SLR makers. This was a short lived camera that is very hard to find today.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/1.7 Mamiya-Sekor EF coated 6-elements in 4-groups

Lens Mount: Mamiya ZE Bayonet

Focus: Variable if SLR, 2.6 feet/meters to Infinity with Click Stops for Portrait, Group, and Scenery, Auto Focus

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism w/ Red LED Display, 93% Field of View, 0.86x Magnification

Shutter: Seiko MFC Vertically Traveling Focal Plane

Speeds (Automatic): 16 – 1/1000 seconds, step less (the manual suggests 22 seconds is the minimum speed, but this appears to be incorrect)

Speeds (Manual): B, 8 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: TTL Center Weighted Gallium Photo Diode with Programmed/Aperture/Shutter Priority “Crossover” AE

Battery: (2x) 1.5v SR44 Silver Oxide Batteries

Flash Mount: Hot shoe and M and X Flash Sync, 1/60 X-Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer, DOF Preview, Viewfinder Blind, Shutter Lock, Battery Check Button, Optional Motor Drive and Remote Shutter Release

Weight: 615 grams, 466 grams (body only)

Manual: https://www.butkus.org/chinon/mamiya/mamiya_ze-x/mamiya_ze-x.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Mamiya ZE-X is a unique SLR from the early 80s featuring a new take on auto exposure, called Crossover AE. In this mode, the camera acts like both aperture or shutter priority modes, allowing you to choose any combination of f/stops or aperture that you like, so as long as it will result in a proper exposure. If the camera’s metering system disagrees with your choice, it will pick something else for you. This seemingly “idiot proof” system worked quite well, but was not well received by the public as this camera sold poorly. Despite that, it is a well designed, and easy to use SLR that is capable of excellent images. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +1 for an innovative AE system that no one else offered and worked well | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.0 | ||||||

The first words that come to mind when I think of the Mamiya Auto XTL Mamiya ZE-X are ones that I feel like I’ve said recently and they are “Another SLR, another lens mount.”

And I did just say those words on many reviews on this site, such as the Mamiya Auto XTL, Rolleiflex SL35, AGFA Selectaflex, Minolta Vectis S-1, and many other SLRs, all of which have a dead end lens mount used on a very small number of cameras.

Like those cameras, the Mamiya ZE-X used a proprietary ZE bayonet that was introduced in 1980 on the Mamiya ZE, and used on only four different models, the most advanced of which is this ZE-X. The ZE bayonet is physically similar to the Mamiya CS mount, introduced in 1978 on the Mamiya NC1000 and used on only one other model, the similarly named NC1000s. The CS lens mount was designed for auto exposure, but only supported shutter priority and manual exposure modes.

Prior to the NC1000, Mamiya created a variety of 35mm SLRs with a huge variety of lens mounts. In the 1960s and 70s, they bounced back and forth between models using a Mamiya specific M42 screw mount called the SX mount with models in the MSX and DSX, models using the universal M42 screw mount in the TL and DTL series, but in 1971 and 1975 respectively released advanced models called the Auto XTL and Auto X-1000 which used an entirely unique bayonet lens mount.

Going back even farther, Mamiya produced cameras that used the Exakta bayonet, Nikon F bayonet, a model called the Argus SLR which used it’s own unique lens mount, and another leaf shutter SLR called both the Mamiya Prismat PH and PCA Prismat V-90 with yet another unique lens mount.

If you’re keeping score, in the years between 1961 and 1981, they created cameras using nine different lens

Why exactly Mamiya couldn’t stick to a single mount might have to do with the fact that their earliest successes were in folding cameras and then twin lens reflexes such as the C-series, and medium format SLR series of cameras including models like the Mamiya M645. Perhaps the leadership at Mamiya didn’t want to commit to a single 35mm system, and whoever was in charge at whatever time they were planning a new model, decided they wanted to use something new.

Throughout the 1960s, Mamiya’s SLRs were a mish mash of Mamiya branded models and rebranded models made for other brands. While all were built with a good level of quality, none were especially innovative. It wouldn’t be until 1971 with the release of the Mamiya Auto XTL did it appear the company was serious about 35mm SLRs.

The Auto XTL was an ambitious camera that Mamiya added many state of the art features such as a switchable 6% spot/averaging meter that took readings at the film plane, an exposure hold switch, shutter priority automatic exposure, and the most information filled viewfinder of any camera at the time. The idea of taking a light reading at the film plane was first available in the fixed-mirror Canon Pellix, but also in the very successful Olympus OM-2 from 1975, four years after the release of the Auto XTL. Taking a reading exactly where light meets the film is more accurate as slight variances in light traveling through a prism and the possibility of stray light entering through the rear viewfinder can negatively affect the reading in traditional SLRs.

The Auto XTL’s innovative and long list of features also increased it’s price. In 1971, list prices with f/1.8 and f/1.4 lenses were $319.50 and $349.50 respectively which when adjusted for inflation, compare to around $2300 and $2550 today, certainly higher than that of a typical consumer 35mm SLR. Although they were well built cameras with a long list of features, they were both too expensive for casual photographers and too risky for the pros.

A second model using the Auto XTL’s lens mount called the Auto X-1000 was released in 1975, but it too sold poorly, and by then, Mamiya had already gone back to releasing consumer grade SLRs using the M42 screw mount.

In the late 1970s, Mamiya would try again with a new 35mm SLR with modern features which was called the Mamiya NC-1000. This new camera was very compact and light weight, yet featured advanced features like an electronically timed shutter, shutter priority auto exposure, and a selection of accessories including interchangeable viewfinder screens.

The NC-1000 and it’s follow-up the NC-1000s were a modest success, but for reasons we may never understand, in 1980, only two years after the model’s release, Mamiya would abandon the series, replacing it with a new model called the Mamiya ZE, using yet another bayonet lens mount. The new ZE bayonet mount used the same physical mounts, but had internal electronic connections allowing the camera to communicate with the lens without the use of physical linkages. This allowed Mamiya to introduce new features never before seen on a 35mm SLR.

The Mamiya ZE was the first model in this new series, but was followed up by the ZE-2, ZE-X, and in 1982, the ZM Quartz which was both the last in the series and the last 35mm SLR Mamiya would ever make. The ZE series was aimed at the middle of the consumer grade SLR spectrum, with the basic model and the most advanced, the ZE-X sold at the same time.

A prototype of the Mamiya ZE-X made it’s debut at Photokina 1980 prompting the short preview to the left from Modern Photography’s 1981 preview issue. In it, the editors were intrigued by the promise of auto exposure modes with “many differences”.

When it was released the following year, it was a technological tour de force, competing against premium models like the Canon A-1 and Minolta X-700. Mamiya further added two additional features that were not available on any competing camera. The first was what they called Crossover Auto Exposure, which was a sort of safety net for both shutter and aperture priority auto exposure modes.

The new Crossover mode had two primary benefits. The first, is that in aperture or shutter priority modes, the camera would obey whatever shutter speed or f/stop you’ve manually selected and pick a corresponding setting for proper exposure with the available light. If however, your manual selections were out of the range of what the camera could select, it would override your setting and pick an f/stop and shutter speed that would. It’s second function was that in both aperture and shutter priority modes, but also programmed auto exposure modes, it would make an attempt to pick the fastest shutter speed possible to avoid body shake. So for example, if the programmed mode detected that an 1/15 second shutter speed was required, it would first attempt to pick a larger f/stop so that a faster shutter speed could be used. Only when no larger f/stop was available would a slower speed be used. This type of protection against body shake was pretty common in most 80s and 90s automatic SLRs, but was pretty advanced for 1981.

All of the benefits of the Crossover mode could be disabled, forcing the camera to choose whatever you have selected, but then you could still get incorrect exposures if you went beyond the physical limits of what the camera was capable.

The second new feature of the ZE-X required the use of newer Mamiya-Sekor EF lenses which had the ability to communicate the chosen focus distance back to the camera’s body. When using a compatible Mamiya flash gun, the flash power and auto exposure mode would adjust for whatever distance you have focused the lens to. So, in other words, if you are focusing on something 3 feet away, the exposure system will adjust for the flash at that distance, at 10 feet away, it would require more light for a proper exposure.

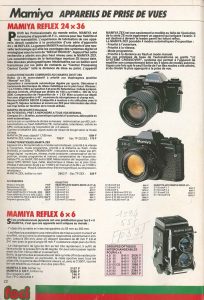

A total of 20 lenses were made using the Mamiya ZE bayonet, most of which were branded as Mamiya-Sekor E lenses and four more called EF lenses which supported the a few additional features built into the ZE-X.

In the March 1982 edition of Popular Photography’s first look at the Mamiya ZE-X, the price is listed with a 50mm f/1.4 Mamiya-Sekor EF lens for $600. In a later article from December 1983, the price with the same lens was lowered to a still not insignificant $515. When adjusted for inflation, these prices compare to $1880 and $1550 today, both prices consistent with that of advanced “pro-sumer” digital mirrorless cameras today.

A second article from the December 1983 issue of Popular Photography went into greater detail than the first article, offering a strip down report of the innards of the camera, investigating the technology used and how it worked. This article is much more technical in nature, but offers some insight into future plans for the series that Mamiya had possibly envisioned, had the camera been more successful.

As they had a long history of doing, cameras from the Mamiya ZE-series were rebadged and sold under a variety of names. The Mamiya ZE was also sold as the Bell & Howell .Z and Revue AM Quartz, the Mamiya ZE-X as the Revue X4-M Multi Program, and a the Mamiya ZM as a new version called the Voigtländer Bessamatic. It is rumored that as many as 20 of these Voigtländer versions of the Mamiya ZM were made, none have ever been seen. A mockup of what it might have looked like can be found online, but it just a mockup and not a real camera.

The factors that likely caused Mamiya to jump around so much from lens mount to lens mount, likely caught up to them in 1983 as the entire company would succumb to lingering financial troubles and concentrate only on their medium format cameras, which were still selling well. The Mamiya ZE-X and ZM would end up being the company’s last two 35mm SLRs.

According to an article in the December 1982 issue of The British Journal of Photography, a new model called the Mamiya ZF was supposedly in development around the time Mamiya ended production of 35mm SLRs. No pictures were shown of such a model, but Mamiya fan, R.L. Herron describes it as:

It was described as similar in appearance to the ZM, but with a larger left-hand handgrip to house four AAA batteries needed to operate a lens autofocus control. There was also a green LED at the bottom of the finder, to show correct focus. Yet another LED was designed to indicate insufficient light for a reliable sharpness measurement.

Today, Japanese SLRs from the late 1970s and early 1980s are attractive to collectors and those looking to get back into, or try film for the first time. This generation of cameras have a good balance of modern features like automatic exposure, electronic shutters, and full information viewfinders that won’t seem too intimidating to someone who grew up in the digital era, but still offer enough manual control to give the full experience of shooting an old camera.

If you were to make a list of the most recommended SLRs from this era, models by Canon, Nikon, Pentax, Minolta, Konica, Yashica, and others would likely all come before Mamiya. While Mamiya made quality optics and cameras as good as their competitors, they just weren’t as well known. I doubt if someone made a list of the top 10, 20, or even 50 SLRs, the Mamiya ZE-X would be on it, but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth considering. These aren’t common cameras to find, but if you do come across one in good shape, for a reasonable price, you would be missing out if you didn’t give it a try!

My Thoughts

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, like most people I was stuck at home with nothing more to do than sit and obsess over the cameras in my collection. I had been shooting the Minolta XD11 around that time and loved it’s combination of advanced modern features, with old school manual everything control. A similar camera from the same era that eluded me was the Canon A-1. I knew that both it and the XD11 were from the same era and had some overlapping features so I set my sights on one.

Then one night while browsing everyone’s favorite place to buy old cameras, I stumbled upon an interesting camera that I had never seen before. It was a manual focus Mamiya SLR with a small built in hand grip, a red LED display in the viewfinder, and a bunch of different exposure modes. The camera of course, was the Mamiya ZE-X. I had seen other ZE cameras like the ZE Quartz and ZE-2, but never the ZE-X and I became intrigued. The more I read about them, the more I wanted them and that desire quickly caused me to forget all about the Canon A-1.

Soon, I had in my hands a working ZE-X body, but no lens. As I would learn, Mamiya made 20 lenses in the mount and they aren’t that hard to find, but wanting to use the camera to it’s full strength, I wanted an EF lens. Finding a Mamiya EF lens is not as easy as it sounds. Sure, they’re out there, but they are often misidentified, and when they are identified correctly, the prices are usually unrealistically high.

I’ll save you the boring details and skip ahead a year to when I finally had in my hands a complete Mamiya ZE-X with 50mm f/1.7 EF lens. The camera was in excellent condition and everything seemed to work, even the super cool red LED display.

Holding the Mamiya, it is clear that this isn’t just any run of the mill Japanese SLR. The camera is compact and very light weight. Where some manufacturers like Minolta and Canon tried to hide the fact that plastic was more and more being used in a camera’s construction, Mamiya makes no attempt to hide the camera’s light weight construction. I should clarify that the camera doesn’t feel cheap, it just feels light weight. At a total combined weight of 615 grams with the lens and an incredibly light 466 for just the body, the ZE-X has a feature list MUCH longer than other camera’s of it’s size.

The Mamiya ZE-X has a blend of old and new. On one hand, all of the familiar controls you’d expect from an early 1980s manual focus SLR like a rapid wind lever, a shutter speed dial with manual shutter speeds, a couple of exposure switches, a film reminder ring, and a fold out rewind knob, but what’s interesting is the smooth electromagnetic shutter release that both acts as a power switch for the camera’s metering system and shutter release, not unlike the one found on the Minolta XD11.

The entire right side of the camera, including the film advance lever, shutter speed dial, and shutter release are all molded into a flat design that all works together that had the camera not had a pentaprism, could sit upside down on a flat surface without toppling over. The film advance lever has a 130 degree total motion with 30 degree standoff and is non-ratcheting, which means it requires a complete motion per exposure instead of using several smaller strokes.

The shutter speed dial is large and very easy to use and has speeds from 8 to 1/1000 plus Bulb and a green Auto mode. According to the ZE-X’s manual, a rectangular button to the left of the shutter speed dial must be pressed to turn the shutter speed dial away from Auto mode, however on the example I had, this button must be pressed to make any change to shutter speeds. I am uncertain if this was a mistake in the manual, if a mid-model update to this camera changed how this button worked, or if my example is broken somehow. I’d like to believe that my example is just broken because having to press an unlock button to make any change to shutter speeds is very annoying.

The shutter speed dial shares a design characteristic I love which is that it overlaps the front edge of the camera slightly, allowing your right index finger to spin the dial on it’s front edge, without ever having to lower the camera from your eye. Other cameras like the Canon EF, Leica M5, and Nikon FG all share this feature, and it’s something I wish existed on more cameras.

The camera’s left side is a little less interesting with the traditional looking rewind knob and fold out handle. Beneath is the ASA film speed dial with settings from ASA 6 all the way to 3200. To change film speeds, lift up on the outer ring and rotate it until a white mark is opposite of your desired speed and then let it fall back into place. The film speed ring also doubles as the exposure compensation dial which offers settings from -3 to +3 which is unusual as most cameras stop at +/- 2. To change the EV setting, you must first press and hold the lock button below and to the right of the dial and rotate the entire dial. With any setting other than 0 set, the letter “V” will appear in the viewfinder LCD to indicate that exposure compensation is on.

The bottom of the Mamiya ZE-X is unusually busy for a 1970s Japanese SLR, featuring centrally located metal 1/4″ tripod socket in the center and the rectangular opening for the battery compartment. Two 1.5v silver oxide or alkaline SR44 or LR44 batteries are used to power the camera. The ZE-X is fully electronic and will not work without fully charged batteries, offering no mechanical operation. A grid of eight electrical contacts, a geared metal rewind gear, and circular opening are all used for the optional Mamiya Winder ZE which offers motorized film advance up to 2 exposures per second. A circular connection port on mine is missing the round cap that is supposed to protect it. You can see tape residue where some previous owner tried to cover it up.

One last thing to see on the bottom of the camera is actually on the bottom of the lens. A small switch to the right of the lens serial number that only appears on Mamiya EF lenses is the focus distance priority switch. This feature of EF lenses enables the camera’s ability to automatically control the aperture based on focus distance when shooting with compatible Mamiya flash units.

The sides of the Mamiya ZE-X body are uninteresting save for the forward angled strap lugs. Having the lugs in this location allows the camera to hang more evenly with a lens attached.

From the right side of the camera, you can see the round exposure memory button on the side of the mirror box which is used to hold a measured exposure so that you may recompose your image when shooting into a strong foreground or background light. Also visible from this side of the camera is the sliding self-timer switch on the right angle of the front finger grip.

Around back, the rectangular eyepiece for the viewfinder has slots for various viewfinder accessories available. To the left of the eyepiece is the viewfinder blind switch. With the blind closed, light cannot enter through the eyepiece which can negatively affect the auto exposure system while shooting in low light or while using the self-timer. To the right of the eyepiece, beneath the film advance lever, is a double image exposure switch. For intentional double exposures, push the slider to the right and hold to deactivate the film transport while cocking the shutter by winding the film advance lever. Once the shutter is cocked again, release the double exposure lever and make a second exposure on top of the previous exposure. You can make as many exposures as you light over the same piece of film by repeating this process.

The film door is opened by lifting up the rewind knob and giving it a rug. The right hinged door swings open to reveal a pretty normal film compartment. Film transports from left to right onto a double slotted take up spool. Film winds onto the spool clockwise, which means that as the film is exposed, it curls opposite of how it is stored in the camera, which is said to help remove some of the curl that naturally happens as film is stored in it’s cassette. Foam light seal material exists inside the door channels and on the hinge side which had degraded in this camera and needed to be replaced before I could shoot it.

Above and to the left of the film gate is a small round electrical contact which does not connect to anything on the standard door back and was likely intended to be used with some sort of accessory data back. The film door is removable via a metal pin in the hinge, further suggesting multiple backs were considered or even developed for the ZE-X, but none seem to have ever been released. Below this metal contact, also on the left side of the film gate is a small pin that is pressed in when film passes over it. This is used by the camera with a motor drive attached to know when the film has been completely rewound into the cassette, so the motor can stop spinning.

The Mamiya-Sekor EF 50mm f/1.7 lens that I had mounted to the camera works similarly to other SLRs of the same era. A decently large focus grip near the front edge of the lens allows for easy focus control. A full sweep from minimum focus to infinity takes about a third of a rotation which is just enough to be possible with a single movement. The aperture ring is closest to the camera body and turns very loosely and offers no resistance when turning. On the plus side, it has firm and reassuring click stops at every stop from f/1.7 to f/16. A depth of field scale is printed in between the focus and aperture scales with an IR focus mark just to the right of f/4.

Fun Fact: Although looking like and working like a standard mechanical aperture ring around the lens, the diaphragm in Mamiya ZE mount lenses are controlled entirely by the camera body. The ring itself has no mechanical linkage to the blades. Turning this dial merely sends a signal through one of the electrical contacts on the body of the camera, and when at the moment of exposure, the camera set’s the f/stop either by what you selected in manual modes, or what it wants in one of the selected auto exposure modes.

A white button to the right of f/16 on the aperture ring is both where you must turn the lens to activate both shutter priority and programmed auto exposure modes, but is also a lock button that must be pressed to get the aperture ring out of these modes.

Up front, the Mamiya ZE-X uses a three lug bayonet mount that is a variation of Mamiya’s earlier mount used on the NC1000 from 1978. It attaches and removes the same as any other bayonet from it’s era. Press and hold the lens release button near the 3 o’clock position around the lens and give the lens a quick counterclockwise twist to remove. Installation is the opposite.

Fun Fact #2: The Mamiya ZE-X body has a total of 16 electrical contacts inside of the lens mount, but no ZE mount lenses have more than 11. In a detailed technical review of the ZE-X from December 1983, it is explained that the 5 pins on the right side of the lens mount communicate data from the lens to the camera. Information like focal length, focus distance, and selected aperture are communicated through here. The first six across the top (the final five are not used) act as switches, probably to be used for other features that were planned but never developed. The inclusion of more pins than lens contacts suggests Mamiya had more plans intended for ZE mount lenses, possibly such as auto focus or image stabilization features.

Above and to the right of the lens release is a rectangular port for an auxiliary left handed shutter release handle that Mamiya made for this camera. There would normally be a cover over the contacts, which has gone missing on this camera. Near the bottom right corner of the front of the camera is a threaded socket that the handle would screw into for added security.

To the left of the lens mount is the finger grip which also has a sliding switch for the electronic self timer. Sliding the self timer switch down reveals three positions for 2,5, and 10 seconds. With the lever at any three positions, pressing the shutter release after advancing the film will fire the shutter after your chosen delay. You may cancel the self-timer simply by sliding it back to the top position. With the self timer activated, an audible beep will be emitted from a tiny speaker on the front face of the camera near the 8 o’clock position around the lens mount.

Looking at the front of the camera, notable omissions from it’s feature set is the lack of both a mirror lockup and depth of field preview. While the lack of mirror lock up likely wouldn’t have bothered too many people in this camera’s segment, I think not having any way to preview depth of field was a big miss as photographers in the advanced consumer market likely would have appreciated such a feature.

One of the more modern features of the Mamiya ZE-X is it’s viewfinder, specifically the red LED display in the viewfinder. If you’ve ever seen a Canon A-1 SLR, the display is very similar. Resembling a late 1970s early 80s calculator, the 7-segment LEDs in the viewfinder are bright and very easy to see, even in bright outdoor scenes. The brightness of the display automatically dims in low light so as not to overpower the light coming through the viewfinder and gets brighter the more light enters the viewfinder so it isn’t overpowered itself. I found that even when shooting in bright sunlight, I had no problem seeing the display.

The display is capable of showing shutter speeds from 1000 to 16″ which is the camera’s full range of speeds. If while in aperture priority or programmed AE modes, the meter cannot detect sufficient light to make a proper exposure, the shutter speed display will blink as a warning. If while in shutter priority AE mode, the meter cannot detect sufficient light, the aperture display will blink.

Although the metering system can select infinitely variable speeds, the display will only show the nearest full stop. So if the meter decides a shutter speed of 1/414 is needed, the display will show 500. The same thing applies to the aperture display which can show only full stops from 1.2 to 16. When using an aperture of f/1.7 or f/3.5, it will round up or down to the nearest number it is capable of displaying, even though the correct aperture will be used.

A few other symbols can appear in the viewfinder such as a small letter V, which shows when any type of EV compensation is being used. A small degree symbol will appear when the Crossover function is being used, notifying you that your settings have been overridden, a capital P for Programmed AE, the letters EF to indicate that EF mode is enabled on supported lenses, a lower case m to indicate maximum flash distance has been used, and finally, a capital M to indicate the camera is in full manual. In full manual mode, the metering circuit and the rest of the display is off, so you cannot see your selected shutter speeds or f/stops through the viewfinder.

The Mamiya ZE-X was a mix of old and new. A manual focus camera that could be operated as manually as you wanted, but it also had a huge array of exposure modes and advanced features which were not common. On the showroom floor, the camera’s unique looks, excellent ergonomics, Mamiya’s excellent reputation as a lens maker, and the camera’s state of the art features likely make it a camera many drooled over. I know I did when I first saw one, but how does it shoot?

My Results

For the first roll of film in the Mamiya ZE-X, I chose some Rollei RPX 25 that I had picked up a 100′ bulk roll of. Although I have shot this film since, the ZE-X was the first camera I had used it in. I love slower black and white films for their almost invisible grain, and despite the slow speed, works well on cameras with fast sub f/2 lenses. As this was my first ever roll of RPX 25, I was unaware as I was shooting it how contrasty it would be. This wouldn’t end up being a problem, however, it did alter the look of some of the exposures more than I had intended. After seeing the results from the Rollei film, I shot a roll of fresh Fuji 200 in the camera to get a sense of it’s performance in color.

By the 1980s, pretty much any Japanese SLR was capable of excellent images, and the Mamiya ZE-X was no exception. Images from the Mamiya-Sekor EF 50mm f/1.7 lens were razor sharp. Easily as good as anything that a Nikon, Canon, Minolta, or a dozen other brands could have shot. The black and white images on the normally very contrasty RPX 25 film, were nicely tamed. The fine grain of that film benefits the incredible resolution of this lens. Looking at the images in the gallery above at normal size on a computer monitor, they do not not look much different from black and white digital images shot on a modern DSLR or mirrorless.

The results from the Fuji 200 were mostly great. Sharpness and contrast from the Mamiya-Sekor 50mm f/1.7 lens is excellent from corner to corner. No vignetting was visible even in scenes where the sky was present and there were none of the typical anomalies often associated with lesser lenses. The one issue I did notice on about a third of a roll was a tendency for the camera’s meter to over expose. Considering I left the camera’s signature Crossover feature enabled throughout the entire roll, I shouldn’t have been able to select an incorrect exposure, but a few scenes turned out with blown out colors. I’ll concede that after 40 years of age, even the most advanced electronic camera can miss exposure by a stop or two.

Shooting the ZE-X was mostly a pleasant experience. The compact and lightweight design made it very easy to carry. Although I didn’t take it on long shooting sessions, I would feel confident in saying that a several hours long walk around the zoo with the camera dangling from a strap around my neck wouldn’t have caused any significant fatigue.

The ergonomics of the camera were excellent as well. I liked the flat top of the film advance lever and shutter speed dial. The dial itself extends beyond the front lop of the top plate, meaning it can easily be changed by sliding your finger left and right without ever having to take it away from your eye. This is a design element I’ve praised before on cameras like the Canon EF, and although I’ve never written reviews for them, the Nikon FG and Leica M5 as well.

My favorite “feature” of the camera’s design is the small angled grip on the front of the camera, allowing a comfortable and secure grip of your right hand on the camera. The grip is much smaller than those found on cameras from the 90s and beyond, but despite it’s small size, still gets the job done.

The omission of any way to preview depth of field wasn’t a big deal to me as it’s not a feature I use often, but I suspect photographers in this camera’s target price range would have missed it. By far, the worst part of the camera’s design is the confusing way in which you switch between the camera’s different exposure modes. There is no single PSAM dial like you’d expect on other cameras allowing easy changes between exposure modes. Instead, you have to use a confusing combination of turning the lens to an unmarked white dot on the aperture ring for shutter priority and programmed AE modes, the shutter dial to a green “A” mark for aperture priority and programmed AE modes, and use a sliding “MODE” switch to the left of the prism to enable or disable the Crossover mode. It seems downright strange that for how much Mamiya promoted the Crossover feature of the camera, the switch that controls it isn’t labeled as such.

Once you have the camera in whatever exposure mode you want, the control layout is nice. The camera fits nicely into my hands and I never struggled to reach any of it’s controls. I also loved the red LED display in the viewfinder, as it worked really well and gave the camera a true retro aesthetic.

I did have some concerns about the build quality of the camera and lens as there was a lot of plastic used in it’s construction. At times, the camera would creak in my hands, and although I had no problems with it, I felt as though the film advance lever could be a weak spot of the camera with continued use. The aperture ring on the EF lens is entirely electronic and it feels “disconnected” to the camera when turning it and I found that the lens mount was unnecessarily stiff when mounting and dismounting the camera.

To be fair, we’re talking about a 40-plus year old electronic camera. I shouldn’t have the same tactile expectations of this compared to a Nikon F from the 1960s, but it’s worth mentioning that along with the modern conveniences this camera offers, came a reduction in perceived quality. That this example still works fine, suggests they did a good job, but this is the only ZE-X I’ve ever come across, so it is possible that others out there have not fared as well.

And speaking of the modern conveniences, the camera’s signature feature, it’s Crossover auto exposure mode, is really nothing more than a fancy word for Auto mode. I feel as though in the 1980s, if you were in the market for a fully automatic SLR, you would have just bought a fully automatic SLR and let it do it’s thing. If you wanted control over exposure yourself, you would buy a camera that allows you to do that. I can’t imagine that there were too many people who would want to choose their own settings, but still allow a computer to override them if they made a mistake.

In the year this camera was made, Programmed AE was about as advanced as you could get. In those modes, you had no control over exposure. Many models would let you step down to Shutter or Aperture Priority AE modes, but those wouldn’t step in and correct you if you got it wrong, so that the ZE-X offers a sort of hybrid Programmed AE mode that still lets you pick your settings was kinda cool.

It seems that contemporary reviews of the camera liked the feature, but buyers did not respond at the register as the Mamiya ZE-X was a short lived camera that sold poorly. After it’s release, no other company would build a “crossover” system like it as it simply wasn’t needed. So for that, the Mamiya ZE-X is a relic of a very narrow period of time where the technology existed to give you an idiot proof camera for idiots who wanted to control their own exposure, and for that, I think it is very cool!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Mamiya_ZE-X

http://www.herron.50megs.com/ZE.htm

http://thecamerasite.lauro.fi/01_SLR_Cameras/Pages/mamiyaze-x.htm

Very impressive camera. Found many of them on eBay in various states such for parts only to fully working cameras.

Sadly, that’s common for many of these early electronic SLRs. Try to find a working Konica FT-1…if you can, please let me know! 🙂

To add a little bit of detail: Mamiya produced the ZE-X from March 1981 until August of 1982 and made a little over 50,000 copies combined with both the ZE-X branding and the Revue 4M (sold by Foto Quelle) markings.

This is great info, Bill! I am actually surprised, that 50,000 were made. I would have guessed less as it seems like a very uncommon to find camera today and there’s so little info about them out there.

Seems like a lot but when you consider that Mamiya made over 1/2 million of the 500/1000 TL/DTL series maybe not? Actually, a production of 50,000 would be about the lowest production figure of any 35mm Mamiya model other than the Auto XTL and Auto X 1000. But, you are right, the ZE-X does not show up often. Maybe Mamiya produced 50,000 but never sold that many and who knows what happened to the inventory as Mamiya was going through its financial problems of the early 1980s. Also, just to note, my production figures come from Mamiya factory records.

I’d like to see a sales analysis that compared the manufacturers’ earnings from: New camera body with new and unique lens mount … versus new camera body with legacy lens mount. How many great lenses are gathering dust on the Bay because their mounts died when a particular new camera model failed to conquer the universe … And how many lenses are in daily use because they offer the PK, or M42, or Minolta A, or Nikon F Ai mounts?

That would be interesting to know…what is the upside/downside of coming out with a new mount, vs sticking with something that is already popular. With the benefit of hindsight, I would guess that it almost never worked out. Apart from Canon, Pentax, and Minolta, no company that ever came out with a brand new mount, ended up sticking with it for more than a couple of years. And if I had to guess, which lenses from which mounts are still the most in active use, I would suspect Nikon F mount, then Canon EOS, and finally Minolta/Sony A-mount. Rounding out the top 5, I would guess the K-mount and then M42 in 5th.

For years I have been using my slightly later and much less complicated ZM for a nice way to shoot my 645 glass in a 35mm format. Works great. Good luck finding that adapter though. I do have the 28mm, 35-70mm, and 50mm E series lenses, but I don’t really bother with them as I would rather use my FM2n and my Nikon glass.

Mamiya’s ZE-X crossover feature was later used on the Nikon FA where it was called ‘cybernetic override’. Production of Mamiya 35mm cameras ended when it’s world wide distributor went bankrupt in 1985. This sadly killed the ZF autofocus SLR which looked liked a cross between a ZM and a ZE-X. I’ve owned a ZE-X since 1985 but it failed about 10 years ago probably due to capacitors. I also own a ZM which still works fine.