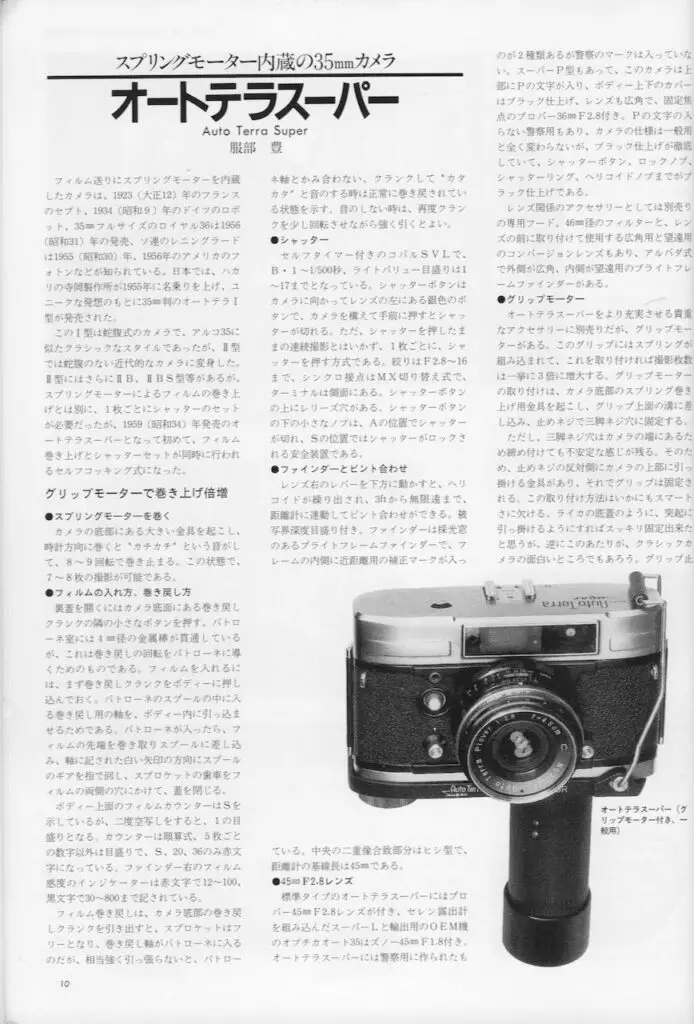

This is an Auto Terra Super, a 35mm rangefinder camera made by K.K. Teraoka Seikōjo in Japan between the years 1959 and 1960. The Auto Terra Super was one of the last and most advanced in a line of Auto Terra cameras made between 1954 and 1960. The signature feature of the Auto Terra series was it’s spring wound motorized film advance. Upon firing the shutter, the camera would automatically advance the film to the next exposure, and on later models, cock the shutter. The Auto Terra Super upgraded the original design so that the film advance also cocked the shutter and also added a coupled rangefinder. Some versions of the Auto Terra also featured an uncoupled selenium exposure meter.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 4.5cm f/2.8 Auto Terra Plover coated 5-elements in 3-groups

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Copal SVL Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and PC port with M and X Flash Sync

Other Features: Shutter Safety Lock

Weight: 840 grams

Manual: https://mikeeckman.com/media/AutoTerraManual.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Auto Terra Super was the most advanced in a line of spring wound 35mm cameras, made by a company known for making scales. Considering it’s non camera company origins, the Auto Terra Super is a fantastically designed camera, both in features and looks. The spring wound motor film transport works flawlessly, the coupled rangefinder is easy to use, the front body shutter release is perfectly positioned and allows for incredible stabilization while shooting the camera, and the 5-element Plovar lens delivers world class results. This is quickly becoming one of my all time favorite cameras, and one I will definitely come back to again and again. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | +1 for innovative design, excellent ergonomics, great lens, the complete package | ||||||

| Final Score | 13.0 | ||||||

History

The origins of the Auto Terra family of spring wound cameras dates back to 1910, when a man named Teraoka Toyoharu founded Nihon Keisanki Seizō or Japan Computer Manufacturing. The company’s business was building adding machines, an early type of mechanical calculator.

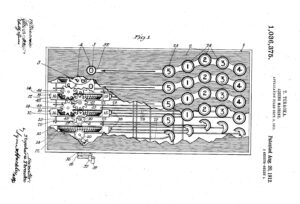

In September 1911, Teraoka submitted patent US1036375A for one of his adding machines. The patent was accepted a year later in August 1912, I could not find evidence that any were actually built. While researching this article, I found a number of sites telling the history of early Japanese calculators, but quickly realizing this was a rabbit hole I was unwilling to continue falling into, I pulled out only to conclude that there was a large industry of Japanese adding machines and calculators, none of which look like the 1911 patent drawing for Teraoka Toyoharu’s machine. If any were built, they either have not survived, or are so obscure that I could not find them.

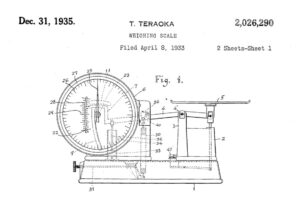

In 1928, Teraoka founded a new company called Asahi Kōki Seisakusho which produced spring scales. The transition from mechanical calculators to spring scales was curious, but at least suggested Teraoka had an aptitude for creating mechanical devices.

It seems that producing scales was more lucrative than calculators as over the next few years, the company manufactured a wide range of scales, both for commercial and household use.

Teraoka’s significant feature of his scales was a temperature insensitive spring that allowed the scale to remain accurate at any temperature. Earlier scales needed to be constantly calibrated for different temperatures as the strength of the spring would change at different temperatures, leading to inaccurate results.

In 1934, Teraoka Toyoharu’s son, Teraoka Takeharu founded another scale producing company called Teraoka Kenkyūjo. What limited information I could find online suggests these were two different companies, but my own personal opinion is that the younger Teraoka took over his father’s business as it does not seem plausible that a father and son would both operate two competing businesses in the same industry. A company history page on the modern day website for the Japanese scale company DIGI, refers to the younger Teraoka as the company’s second president, further suggesting the new company was just a continuation of the elder Teraoka’s company.

In 1938, the company name changed to Teraoka Seiko Co., Ltd. suggesting that it was branching out into other types of precision manufacturing. Teraoka still produced scales, but in the early 1950s, a fondness for cameras inspired Teraoka Takeharu to enter the world of photographic cameras. Using his company’s knowledge of spring wound devices, Teraoka began work on what would become Japan’s first spring wound 35mm camera.

In May 1955, the Auto Terra was presented to the press. The camera had a horizontal folding design, similar to the Japanese Arco 35, first produced in 1952. The Auto Terra had a coupled rangefinder and featured a 4.4cm f/2.8 Plover lens set in a Seikosha leaf shutter with top 1/500 speed. The camera was advertised in 1955 and 1956 issues of Asahi Camera with a price of ¥29,500 which was comparable to cameras like the Aires 35-III which sold for around the same price.

The folding Auto Terra is said to have been produced until April 1957, but despite nearly two and a half years of production very few were made, and even fewer show up for sale today possibly suggesting that the company had difficulties making them.

Further supporting this theory is that in December 1956 a camera called the Auto Terra II appeared in advertisements. It switched to a non-folding solid body. Eliminating the necessary linkages from the spring motor and body mounted shutter release to the moving shutter likely simplified the design.

The Auto Terra II was never put into production however, instead a simpler Auto Terra IIB entered production in early 1957. According to Sugiyama, the only difference between the II and IIB models was the lack of a parallax correcting device. A variation called the Auto Terra IIBS was also produced which upgraded the taking lens to a 4.5cm f/1.9 Plover. One final version of the Auto Terra II called the IIL was produced which added an uncoupled selenium exposure meter.

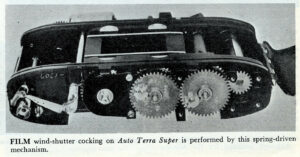

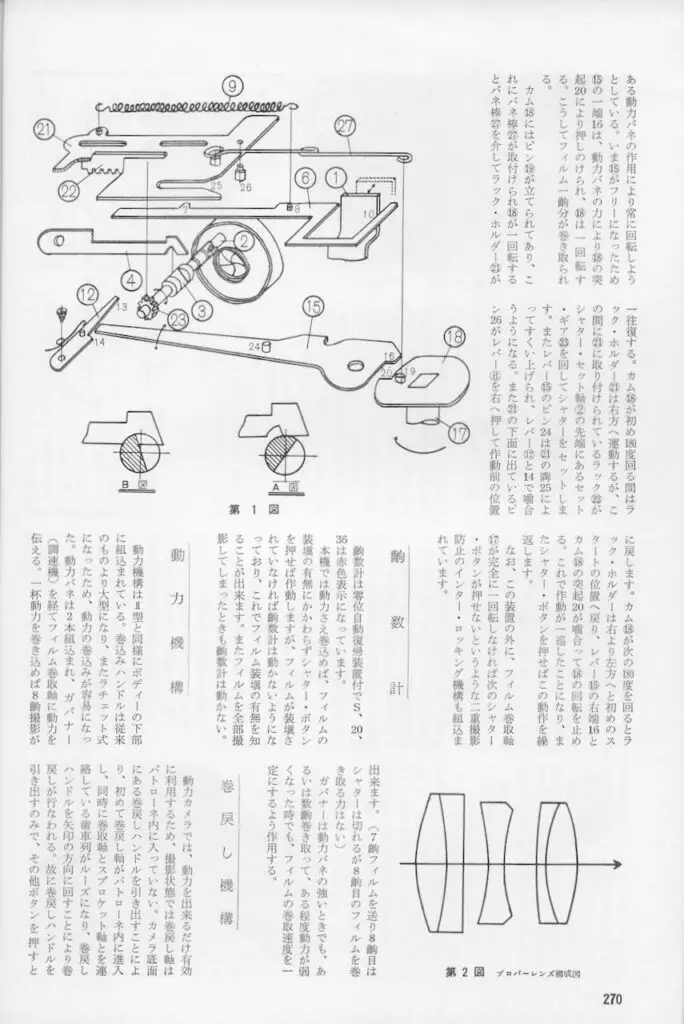

Up until this point, the spring wind mechanism in the Auto Terra cameras was semi-automatic. With the shutter cocked, pressing the shutter release only fired the shutter, but did not trigger the film advance mechanism. This was accomplished via a small lever on the side of the shutter. After each exposure, pressing this lever would cause the spring mechanism to advance the film and ready the shutter for the next exposure.

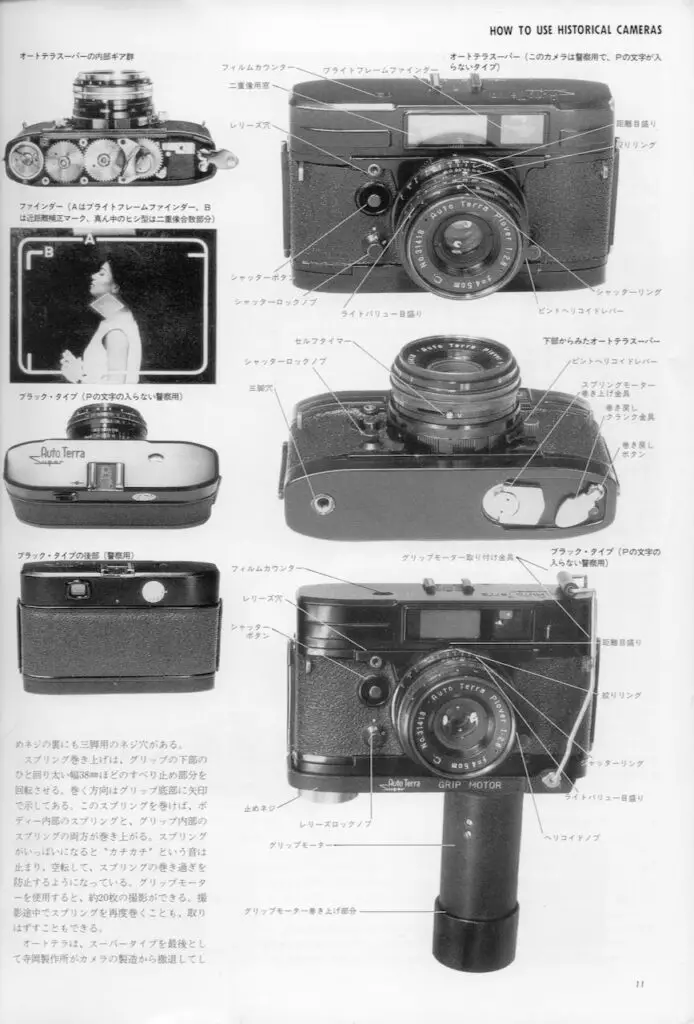

In 1959, Teraoka would revise the spring mechanism, eliminating this extra step with a new model called the Auto Terra Super. With this new model, the Auto Terra was capable of fully automatic film advance. Upon pressing and releasing pressure on the shutter release, the film would automatically advance to the next exposure and the shutter would cock, ready to fire again. In advertisements for the camera, Teraoka referred to this feature as the “Touch-O-Matic” and suggested it was the world’s first one touch magic system, a claim that was clearly false as several other spring wound cameras like the Berning Robot predated it by two decades.

The Auto Terra Super also received an updated viewfinder with a bright line window that projected frame lines within the viewfinder. Other changes included a redesigned top plate and relocated cable release socket.

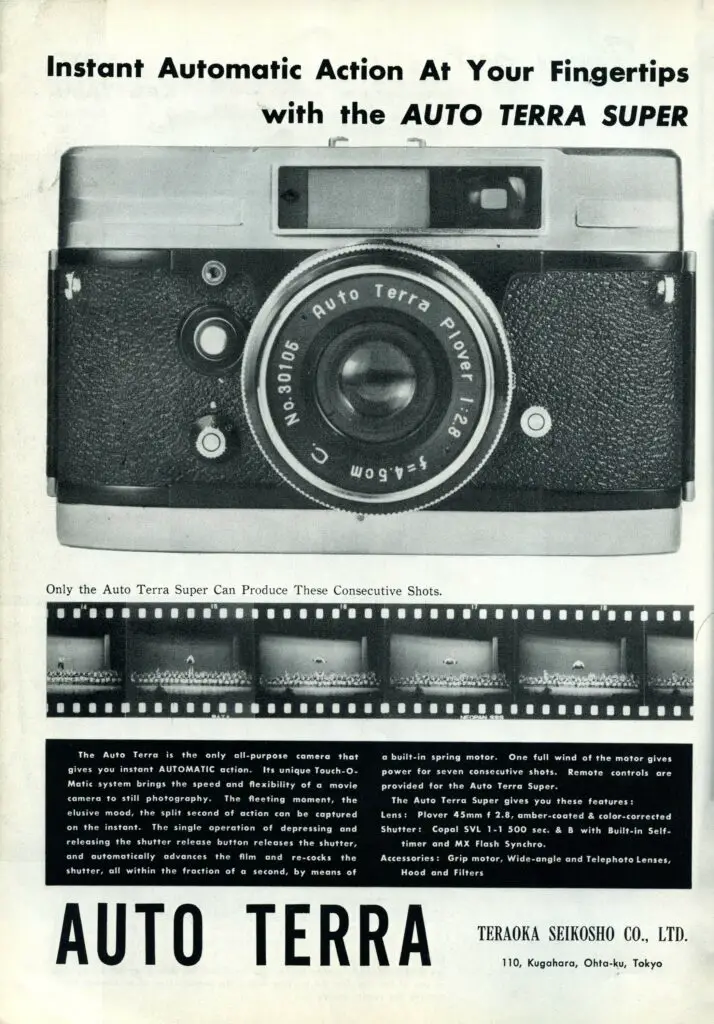

Each of the three ads below all come from 1959 issues of CamerArt magazine, an English language photography magazine published in Japan.

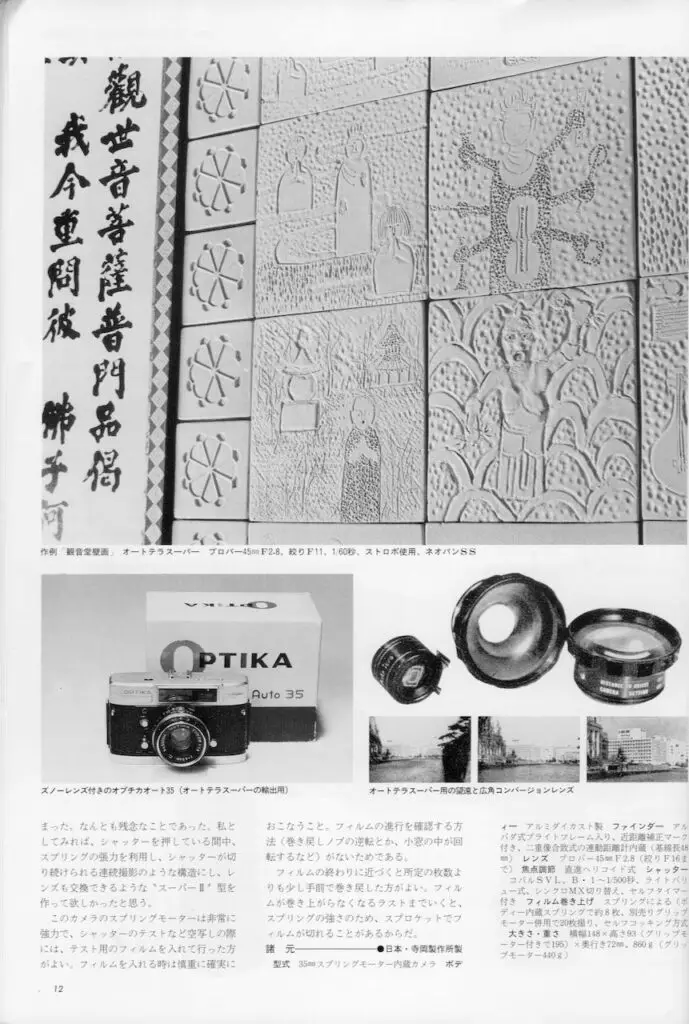

No prices are listed in the ads above, and the only lens mentioned is the 5-element 45mm f/2.8 Plover. Later in the production of the Auto Terra Super, some models with a 6-element f/1.8 Zunow lens have been found, but these are not mentioned in any advertisements I was able to find.

Also in the ads above are auxiliary telephoto and wide angle lenses which screwed onto the front filter threads, altering the focal length of the lens, and a wind up accessory grip motor that allowed for up to 20 consecutive shots. The accessory grip is shown to the right and attaches to the camera by screwing into the tripod socket, and by sliding the folding wind key into a slot in the grip motor.

Contrary to information in the article to the right, continuous exposures of 20 per second are not possible as that would be a stretch even for modern day digital cameras. How exactly the grip drive worked is unclear as it does not couple to the shutter release. You must still press the shutter release after each exposure, but it stands to reason the grip motor winds up with it’s own knob, and it keeps constant tension on the wind up key as you fire the shutter. My best guess is you wind up the camera first, then attach the grip and wind it up, then as you keep firing the shutter and the camera’s internal spring drive winds down, the grip motor keeps advancing the key, until at which point, it’s internal spring winds down, exhausting the total number of consecutive shots.

An export version of the Auto Terra Super exists as the Optika Auto 35. This camera was sold in the United States by a company called Aetna Optix Inc, with an address in New York City that was also registered to the camera retailer Seymour’s which also sold other cameras under the Optika name.

All Optika Auto 35s feature the 6-element f/1.8 Optika Zunow lens, which likely was identical to the version sold on the Auto Terra Super.

The price for the Optika camera was $99.95 with the accessory grip motor drive for an additional $29.95. When adjusted for inflation, these prices compare to just over $1000 and $300 respectively.

Two other variants of the Auto Terra Super were also created, first was the Auto Terra Super L which had an uncoupled selenium exposure meter on the front face of the top plate, similar to the one found on the earlier Auto Terra IIL, but at least one copy is known to have the meter in a circle around the taking lens. The image to the right is the only known image of this second version of the Auto Terra Super L. I could not find any other information about how many were built or why they are so hard to find.

Finally, in 1961, an all black Auto Terra Super P was made for the Japanese police. In addition to having an all black body, the lens on the P model was a wider angle 3.6cm f/2.8 Plover lens and in the few images I’ve seen of one online, they do not appear to have a rangefinder. Only two three of these cameras are known to exist today, but it is thought that up to 40 might have been made. At least one fake example of an Auto Terra Super P has been found which is simply a repainted regular Auto Terra Super.

Edit 1/8/2023: After posting this article, I was contacted by reader Tony Hurst who has a restored Auto Terra Super P and confirmed that it does not have a rangefinder, and that the viewfinder is scale focus only. Tony sent me three images of his camera and with his permission, I am including them below.

For those of you who read Japanese, the following two articles give a little additional insight into the Auto Terra Super, including the possibility that black bodied versions exist. In this first article written by Yutaka Hattori from “Camera Review Classic Camera Senka” number 25, a black bodied Auto Terra Super is clearly shown with the 4.5cm Plover lens. The letter “P” is not visible on the top plate, suggesting this is not a police model.

A second Japanese language review comes from the September 1959 issue of Shashin Kogyo and appears to be a contemporary review of the camera and it’s operation.

Despite being produced for several years, the entire Auto Terra series did not sell well. Although no official records were kept, a study on the serial numbers from known copies of the Auto Terra Super, including the L, Optika, and Police models, suggests that only 2600 were ever made.

The Auto Terra Super would be the last camera made by Teraoka before they exited the camera business. Quite a few reasons could explain their exit, namely low sales, a decrease in popularity of 35mm rangefinders, an increase in competition among Japanese brands, or simply, that Teraoka was never a camera company to begin with.

The company would continue on as a leader in the scale and point of sale industry and still exists today. In 1973, the company would release a line of electronic scales called the DIGI series, a name the company would eventually become known as. The company’s current day website refers to them both as DIGI System and the Teraoka Group. The company is still run by members of the Teraoka family, as their current Chairman of the Board is listed as Kazuharu Teraoka.

Today, cameras like the Auto Terra series are not well known. I had never heard of the series or the company that made them until recently, but for those who have a desire for obscure Japanese brands, spring wound motor drive cameras, or simply, really well made cameras that are fun to shoot, the Auto Terra Super has something for everyone. This is a camera you’re not likely to come across often, but if you do, I strongly recommend taking a good look at it!

My Thoughts

As my collection grows, I sometimes wonder what kind of collector am I? Vlad Kern is a Soviet collector, Ira Cohen doesn’t do folders or 6×6 TLRs, and Johnny Sisson hates Argus cameras. Looking at my shelf of cameras, I have a little bit of everything. Cameras of every shape, size or film format, from every decade of the 20th century, and with any feature.

While looking at some of my favorite cameras however, one style that seems to always come to the top of my favorite cameras are those with wind up clockwork film advances. Cameras like the Kodak Motormatic 35, Fujica Drive, and GOMZ Leningrad check off all of my favorite boxes! There’s something wonderful about a completely mechanical camera that can still automatically advance film and cock the shutter, without the use of batteries.

In the past couple of months, my collection recently grew by two more cameras in this segment, the Konica Auto SE (which I plan on reviewing next year) and the Auto Terra Super.

I had seen an Auto Terra Super while visiting a friend back in 2021, but when I saw one come up for sale in my usual lower end of the price spectrum, I couldn’t resist. These are very cool cameras that not only have the motor wind film transport, but a bright and very useable coupled rangefinder, and a front body shutter release.

The Auto Terra Super is a large and very solid feeling camera. The additional mechanics for the spring wind motor drive certainly add to it’s 840 gram weight and overall size with the base plate a bit thicker than I’d expect to see on a non-motorized 35mm rangefinder from the same era.

Up top the camera has one of the cleanest interfaces I’ve ever seen on a Japanese camera. Aside from an accessory shoe in the center and the automatic resetting exposure counter on the right, the only other thing there is to see is the large and elegant Auto Terra Super engraving. I am quite fond of the typeface used for the camera’s logo with a design somewhat reminiscent of American automobile makers.

When you find a camera with a clean top plate, that usually means there is a clutter of controls on it’s bottom, but that’s not the case here. From left to right is the 1/4″ tripod socket, the folding motor drive wind key, and rewind lever with door release. With a full wind, the camera can make 7 consecutive shots before it needs to be wound up again. I observed that after about the 4th shot, the motor starts to slow down until it gets to the 7th shot, at which point, pressing the shutter release doesn’t do anything. Even though the motor does slow down as it loses power, this has no effect on the shutter speeds, as the shutter will still fire at it’s correct speed, no matter how much power the motor has.

An interesting accessory that was available for the Auto Terra Super was a grip shaped accessory motor drive. The accessory grip motor drive screws into the tripod socket and slides over the camera’s folding wind up key. At least one source online suggests this motor drive was good for up to 20 exposures per second, which is absolutely false as 20 exposures per second is a difficult feat even for modern digital cameras. Rather, the wind up motor drive was said to expose up to 20 consecutive exposures without having to wind up the motor again.

Since the motor drive makes no connection to the shutter release, the speed at which exposures can be made is still limited by how fast the shutter release could be pressed and the camera wind to the next exposure. I am uncertain if the motor drive has a physical limit of only 20 exposures as it would seem it should still work as long as you wind it up for. If I ever come across one, or more information on how it works, I will update this review.

The rewind lever is deserving of some additional explanation as it doesn’t work like most other cameras. Unlike pretty much every other wind up or traditional 35mm camera, there is no button or switch to disengage the film transport for rewinding the film. In fact, the little button next to the rewind handle is the door release, so do not press it with film in the camera! (Ask me how I know!)

To rewind the film, you lift up on the chrome rewind handle and give it a firm tug into a raised position. Doing this both disengages the film transport, but also lowers a fork that grips the inner spool of the film cassette so it can be rewound. Under normal operation, this fork is not connected to the cassette, so I noticed that sometimes when pulling on the rewind handle to get the fork to come out, it doesn’t perfectly line up with the inner spool of the cassette. If this happens, simply turn the rewind handle a little bit and try pulling on it again. You’ll feel the fork engage the inner spool of the cassette so you can begin rewinding it. It sounds complicated, so I made this short video showing how it works without film in the camera.

The sides show a lot of symmetry, mainly due to what appear to be a fake hinge on the latch side of the camera, that almost perfectly mimics the actual hinge on the other side. Both sides of the camera have front facing metal strap lugs which are angled in a way that the camera won’t fall forward when hanging from a strap. Also on the left side of the top plate is the flash sync port which supports both M and X sync.

Around back, the film door is covered with a large swath of body covering. Below it, engraved into the metal is Teraoka’s name and that the camera was made in Japan. Above the door is the rectangular eyepiece for the viewfinder, and to it’s right is a simple film reminder dial that shows ASA color settings for 12 to 100 and black and white from 32 to 400.

The right hinged film door opens to reveal a nicely appointed film compartment. Film transports from left to right onto a single slotted and fixed, metal take up spool. Above and below the film gate are polished metal film rails, with the rest of the compartment painted in a thick matte black paint. Four semi-circle indentations above and below the film gate match up with corresponding semi circle protrusions on the pressure plate on the inside of the film door. These notches are there to prevent any movement of the pressure plate as film transports across.

The pressure plate itself is made of black metal and has a curious combination of horizontal lines and a large X across it, which I can only assume is there to minimize resistance as film transports over it. A chrome metal roller and a black painted spring are on either side of the pressure plate to further aide film as it transports through the camera. Finally, the film compartment uses a combination of black yarn in the door channels and a large piece of black velvet along the hinge side to prevent light from leaking into the film compartment. Neither needed replacement on this copy as they were all in tact and still doing their jobs.

The Auto Terra Super has a Copal-SVL leaf shutter which uses a coupled Light Value Scale. For long time readers of this site, here is where I start to complain about the LVS, but I am happy to say that the one used here is one of the less annoying versions of this feature I’ve seen.

Unlike other cameras like the Voigtländer Vitessa and some versions of the Kodak Retina where the shutter speed and f/stops are linked together with a mechanical pin, the design used here couples both shutter speeds and f/stops when using the outer, black ring. If the red arrow is pointed to 13, and you want to change it to 14 or 12, simply turn that ring and the camera will choose an equivalent exposure for that amount of light. Normally, the black LV ring adjusts f/stops first, allowing you to remain on whatever shutter speed you’ve selected. This is ideal as assuming you need a specific shutter speed to freeze motion and avoid body shake, changing exposure only affects the diaphragm.

If you reach the upper or lower limit of what f/stops are available, and you need a higher or lower LV number, continuing to turn the black dial will then start to raise or lower the shutter speed to match the amount of light. Only when reaching LV 2 and 17 will you have exceeded the mechanical limits of the camera.

The beauty of this system is that with a hand held or clip on light meter, simply set your film speed using your meter, and then program it to give you EV numbers.

LV vs EV: Whole articles have been written about the differences between LV (Luminance Value), and EV (Exposure Value), but in the simplest terms, LV is how bright something is, independent of film speed. EV is how bright something is taking into account film speed. The scale on the Auto Terra Super is LV. You take an EV reading on your light meter, only after setting the correct film speed.

Up front and next to the lens are the threaded cable release socket, shutter release, and a shutter lock dial. This dial has two positions, one marked “A” which I assume means “advance”, and the other marked “S” which probably means “stop”. This is effectively a lock to prevent unintended presses of the shutter release while in storage. The location of the front shutter release is within easy reach of the photographer’s right index finger and pressing the button inward towards the camera helps to stabilize the camera into the photographer’s face which helps to minimize body shake at slow shutter speeds.

The Auto Terra Super’s viewfinder is probably the camera’s least remarkable feature in that it is similar to that of nearly every other 35mm rangefinder of it’s era. There are projected frame lines with parallax correction hash marks, and a diamond shaped coincident image rangefinder patch. The main viewfinder window takes on a bluish green hue and the projected frame lines and rangefinder patch are the color of whatever light enters the bright line window in the front of the camera. On this example, the viewfinder was very clean, but the rangefinder patch was a bit dim.

The Auto Terra Super is a heck of a camera with excellent ergonomics, good build quality, an interesting list of features, and it is attractive. The camera feels very solid and well put together for a model produced by a company better known for making scales than cameras. I have seen much worse cameras produced by far more experienced companies, but the real question you’re asking is, what kinds of results does it make? Keep reading!

My Results

The Auto Terra Super arrived in what appeared to be perfectly working condition. The shutter fired at all speeds, the spring drive appeared to be working correctly, and the rangefinder was accurate at infinity. The camera was a little dirty, so a gentle wipe down with some baby wipes and Q-tips and it was ready to go. I loaded in a roll of Fuji 400 and took it out with me on some every day errands in August 2022.

Upon seeing the excellent results from the color film, I wanted to see what it would do in black and white. For as much as I love color images, I’ve found that black and white films do a better job of showing sharpness and detail in a lens, allowing you to better to see what it is capable of. In hindsight, I wish I had chosen Panatomic-X for it’s almost invisible grain, but TMax 100 is no slouch either, and would allow me to shoot the camera in more lower light situations.

No matter how many times it happens, but that feeling you get when you first take film out of the development tank and can see a whole roll of sharp and properly exposed images, it’s nothing short of magical. As I scanned the images from both films and could see them in their full glory on my monitor, I was blown away at the contrast and sharpness. I rarely like to use the word “rendering” when describing film images, but if you were to show these to me and explain it was shot on a Japanese rangefinder with a f/2.8 lens, I wouldn’t believe it.

The 5-element Plover is quite simply, stunning. Sharpness is excellent corner to corner, both color rendition and black and white contrast is excellent, the lens is devoid of any of the more common optical anomalies. I did notice a bit of softness wide open, as seen in the beer sign and Kodak lamp images, but rather than call it “soft”, I think a better word is glow. I definitely prefer the black and white images over the color ones, but to be fair, I usually don’t get the most amazing images from Fuji 400, especially outdoors.

It is interesting to me that there were faster Plover and Zunow lenses available on these cameras when the f/2.8 Plover performs so well. Perhaps those other lenses were sharper wide open, and of course they have an extra stop of speed, but otherwise, I see no reason to suggest the 5-element f/2.8 lens isn’t a very capable design.

Edit 11/22/2022: Shortly after posting this article, reader Leonid Nikishin took one look at the lens diagram of the 5-element Plover from the Auto Terra Super’s user manual and said it is an almost identical match for a copy of the Voigtländer Heliar. Looking at the two online, I’d have to agree, whoever built the Plover, clearly based it off the Heliar, which is a highly regarded design, further cementing my opinion that the Plovar is a very capable lens.

Shooting the camera was almost as much of a joy as looking at the images it made. The overall ergonomics of the camera are excellent. The tapered and rounded off edges on each side and the size of the body made it fit perfectly into my hands. The location of the front shutter release was exactly where my right index finger wanted to find it. I’ve always enjoyed front shutter release cameras like this as the action of pressing the shutter, further stabilizes the camera into your face, in ways that a top shutter release doesn’t. Of course the spring drive film transport means you never have to move your hands to advance the film, allowing you to keep the camera to your eye and be ready for next exposure without missing a beat.

The Auto Terra Super’s user manual suggests a fully wound spring is good for up to seven exposures, which is exactly how many I got while shooting, so while you can’t go an entire roll without needing to wind it up again, seven exposures is more than enough for most people.

I’ll never admit to loving an LVS system, but the one here is the least annoying version of this feature I’ve found. In fact, when shooting 100 speed film, if you are shooting outdoors in good light, anything from 12 to 15 is going to get you a good exposure, and 8 to 10 is fine for heavy shade.

I have no real complaints about using the camera. I did notice that even though the viewfinder was very clear on this example, the rangefinder patch was a bit dim, but this is perfectly normal for a 60+ year old camera. And if I had one suggestion that might have made the camera even better, would be the ability to continuously fire the shutter like the Bell & Howell Foton, but frankly, I don’t know how many people would use that feature.

The Auto Terra Super is proving itself to be one of my all time favorite cameras. It checks off a bunch of boxes for me, in that it has an attractive design, is from a company with a cool history, it’s not a model you see often, it has a spring wound film transport, excellent ergonomics, and an outstanding lens. What is there not to like?

Sadly, these cameras are not very common and when finding them on the used market, they almost always have pretty high prices, but I can wholeheartedly say that despite a higher price tag, what you get from the camera is worth it.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Auto_Terra_II_and_Super

https://monochrome.ti-da.net/e2526903.html (in Japanese)

https://ameblo.jp/miyou55mane/entry-12427221399.html (in Japanese)

https://www.usedcameracameracamera.com/camera/auto-terra-super/ (in Japanese)

It’s obvious you put a lot of time and effort into this review. Thanks for sharing!

I definitely spend a lot of time on these reviews. The typical review takes me between 3-5 months to write from start to finish. I usually have between 12-15 going on at once though and I jump around between them!

Mike,

Great revue of this quite rare seies of cameras. I have been collecting Auto Terras for about a dozen years and have 6 different models with a couple of doubles. Also have found the Grip and the Tele-Wide lens combination. Love their style and very subjectively have found the Zunow equipped models to have produced slightly better images than the Plover, but there was a Plover F/1.9 on the IIBS and IIL. Anything labelled Zunow is going to dramatically increase the price, and maybe rightly so as their glass has taken on an almost mystical quality and price over the years. I’m glad you have discovered the beauty of this camera and how much fun it is to use.

Regards, Gary Hill

Hi, Enjoyed your Auto Terra article. This confirms the Auto Terra Super P has no rangefinder. I acquired a very beat up version that needed some guess work to restore it. Cheers Tony

Very cool Tony! Send me some pics and I will add them to the article!