This is a Zeiss-Ikon Icarex 35 CS, a 35mm single lens reflex camera produced by Zeiss-Ikon in Braunschweig, West Germany starting in 1968. The Icarex series was originally developed in the early 1960s by Voigtländer as the Bessaflex prior to that company’s merger with Zeiss-Ikon in 1965. When the camera was renamed Icarex, the body received a refresh and featured a selection of Carl Zeiss lenses. The Icarex 35 CS uses a unique breech lock bayonet lens mount and has an all new cloth focal plane shutter, making it Zeiss-Ikon’s second 35mm SLR with a focal plane shutter after the Contarex. The Icarex 35 CS is an update to the original model, adding a removable metered prism and interchangeable focus screens. Later versions of the Icarex series were released with the M42 screw mount with the letters “TM” in the model name.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/2.8 Carl Zeiss Tessar coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Lens Mount: Icarex Breech Lock Bayonet

Focus: 18 inches / 0.45 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Interchangeable SLR Pentaprism with Aperture Preview and Match Needle

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1/2 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: Uncoupled CdS Cell in Prism

Battery: 1.35v PX625 Mercury Battery (for Meter Only)

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and F / X Flash Sync, 1/60 X-sync

Other Features: Interchangeable Focus Screens, Self-Timer, Depth of Field Preview

Weight: 990 grams, 792 grams (no lens), 644 grams (no lens or prism)

Manual (in German): https://www.cameramanuals.org/zeiss_ikon/zeiss_ikon_icarex_35-german.pdf

Manual (Similar Model, in English): https://www.cameramanuals.org/zeiss_ikon/zeiss_ikon_icarex_35_35s.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Zeiss-Ikon Icarex 35 CS was a last hurrah for German SLRs. Originally designed by Voigtländer, when released by Zeiss-Ikon, the camera had a very high build quality and a selection of some of the best lenses ever made. The camera has very modern ergonomics, similar to Japanese SLRs of the same era, a bright viewfinder, and a reliable shutter. The metering prism of the CS is uncoupled and slows you down quite a bit, making it a challenge to use. Aside from that though, as a fully manual, unmetered SLR, it does not get much better than this. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.8 | ||||||

History

The German camera industry has a long history making some of the most successful and historically significant cameras ever made. From the end of the 19th century, companies like Carl Zeiss and Voigtländer were way ahead of anyone else in the world in the photography and optical world. By the first decade of the the 20th century, many of the most successful lens formulas like the Tessar, Heliar, and Planar had already been invented. These formulas were the basis for many lenses still produced today, more than a century later.

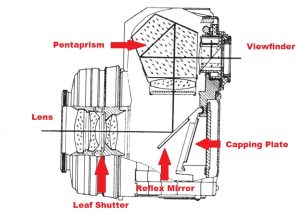

As the decades passed, certain patterns emerged. First were a huge variety of folding bellows roll film cameras with leaf shutters, the 1930s saw the rise of 35mm rangefinder cameras like the Leica and Contax, both with focal plane shutters (although completely different designs), medium format Twin Lens Reflex cameras in the Rolleiflex style, and after the war, West German 35mm Single Lens Reflex cameras with leaf shutters.

In that last category were a huge number of options, from the Kodak Retina Reflex, AGFA’s various -flex models, the Voigtländer Bessamatic and Ultramatic series, the Zeiss-Ikon Contaflex, and even some lesser known models like the Braun Paxette Reflex and Wirgin Edixa Electronica.

There were two reasons West German camera makers had a strong preference for leaf shutters. The first was that Carl Zeiss had a controlling interest in both Deckel and Gauthier, makers of Compur and Prontor shutters. Although never marketed directly as a Carl Zeiss (or later Zeiss-Ikon) product, as one of the most influential German optics companies, the use of either Compur or Prontor shutters was a way smaller companies could “play nice in the sandbox” while also saving on development costs.

The second reason was that Ernst Leitz produced the most well respected focal plane shutter for their Leica rangefinders. Although Leitz would lose it’s patent after the war on the shutter used in the screw mount Leicas, there was an unwritten rule that other West German companies wouldn’t compete with Leitz. With the exception of Wirgin’s focal plane shutter Edixa SLR, all other focal plane shutter SLRs were made in East Germany who didn’t quite have the same level of reverence for German tradition.

As preferences for SLR cameras over rangefinders grew in the 1950s and 60s, companies looking to add a reflex camera to their lineup usually went with some type of Compur or Prontor shutter. Although many leaf shutter SLRs were high quality cameras with excellent lenses, they had several shortcomings.

The first was complexity. Leaf shutters had been used for many decades in many folding, rangefinder, or scale focus cameras. For them to work in an SLR required an additional level of gearing so that the shutters could remain open to let light pass through the lens, reflect off the mirror, and into the viewfinder, while not exposing the film, and through the use of something called a capping plate, would require a complex symphony of levers, gears, and strings to close the shutter, flip up the mirror, open the capping plate, and then fire the shutter to expose the film. This not only added complexity to the construction (and eventual repair) of the cameras, it also increased cost. Another shortcoming is the relatively small opening of most leaf shutters meant that very few wide angle or fast lenses could be used. It was practically impossible to design a lens for a leaf shutter SLR wider than 35mm or faster than f/1.8.

As the Japanese camera industry gained dominance in the 1950s, first with rangefinder cameras, but eventually 35mm SLRs, it became more and more clear to West German camera makers to get with the program and release models with focal plane shutters. Zeiss-Ikon Stuttgart was the first with the Conatrex, an incredibly complex and high quality focal plane shutter SLR. The Contarex was a success in the sense that it proved to the world that a high quality West German SLR was viable, but it was far too expensive for most people to afford.

For their next attempt, we need to go back to 1956 when Zeiss-Ikon purchased Voigtländer AG from Schering AG. After acquiring Voigtländer, Heinz Küppenbender became technical director at Zeiss-Ikon Oberkochen and oversaw projects at both companies but allowed both Voigtländer and Zeiss-Ikon to continue to operate separately with their own factories, research, and design.

In the early 1960s, Voigtländer’s lineup of 35mm SLRs already had two high priced models, the Bessamatic and Ultramatic. The company was facing increased competition from more economically priced Japanese models, so an order was given to Voigtländer’s chief designer Walter Swarofsky to build an all new affordable SLR with a price no higher than 400 DM which could compete with the new market of Japanese SLRs.

In late 1962, Swarofsky, along with this team consisting of Fritz Renneberg and Kurt Barke got started on an all new camera. A focal plane shutter was chosen not only to compare to the Japanese models, but also to keep the costs down as by then, a focal plane SLR was easier to build than another leaf shutter.

It would take less than a year for the team to come up with a working prototype of the Bessamatic prototype which accomplished all of the team’s goals, most notably a cloth focal plane shutter, an all new breech lock bayonet lens mount, and a design similar to Japanese SLRs.

A small number of finished prototypes were produced, presumably to debut at trade shows, but sadly, before the camera could reach a more widespread production, work on the new camera was stopped by Heinz Küppenbender as it was thought that too many of Voigtländer and Zeiss-Ikon’s models would compete with each other.

In 1964, a slightly revised Contarex called the Model D was being released which added support for interchangeable focusing screens, an expanded range of film speeds, a revised meter baffle, and a new feature allowing the photographer to insert strips into the film compartment to uniquely identify rolls of film.

Despite these updates, the Contarex sold slowly, most likely due to it’s extremely high price tag. As of January 1962, the price of a Contarex with the f/2 Planar lens was $499, which when adjusted for inflation, compares to a little over $4900 today. It was clear to Zeiss-Ikon that they needed a more consumer oriented camera to compete with growing selection of affordable, and well built Japanese cameras. The Contarex was far too complicated for them to find a way to simplify it for sale at a lower price, but starting over from scratch with an all new model was too time consuming, so the company took the nearly completed Voigtländer Bessaflex prototype, made some cosmetic changes to it, gave it a new name, and in 1965, released it as the Zeiss-Ikon Icarex 35.

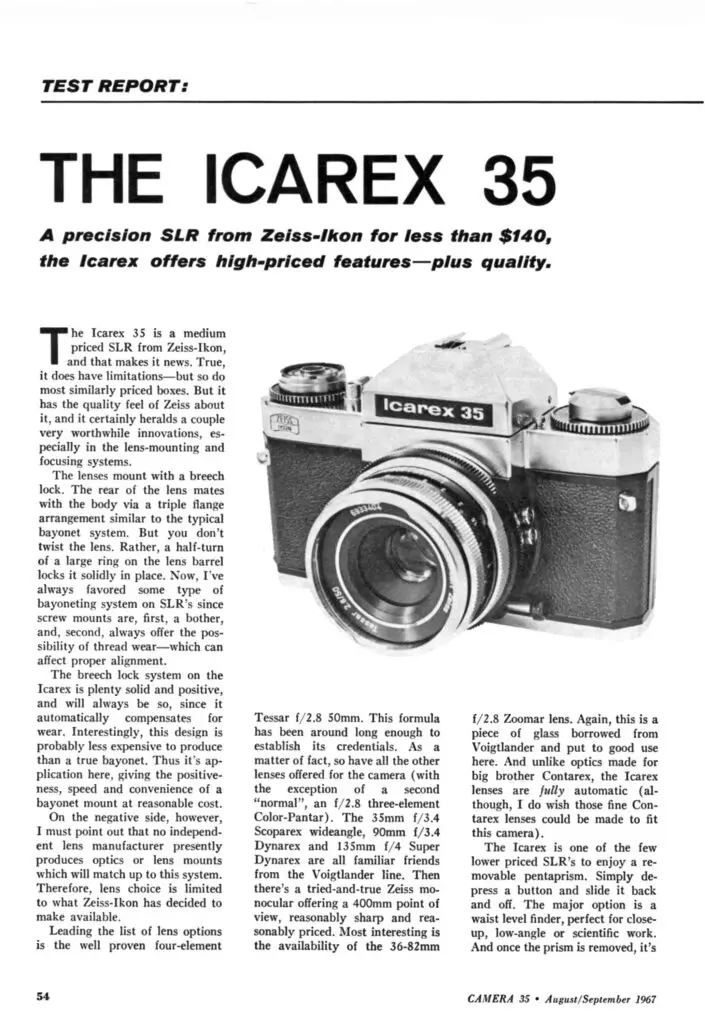

The Icarex was a fine camera, featuring the features and build quality developed for the Bessaflex. It retained the same lens mount, interchangeable viewfinder, cloth focal plane shutter, and the same Japanese-esque control layout. Perhaps the biggest difference was the price. With a retail price of $139 including a 50mm f/2.8 Tessar, the Icarex 35 was less than half the price of the Conarex and still less expensive than the Voigtländer Ultramatic which was still in production. This allowed the Icarex to be considered by a much larger group of potential customers who previously might have never considered a Zeiss-Ikon SLR.

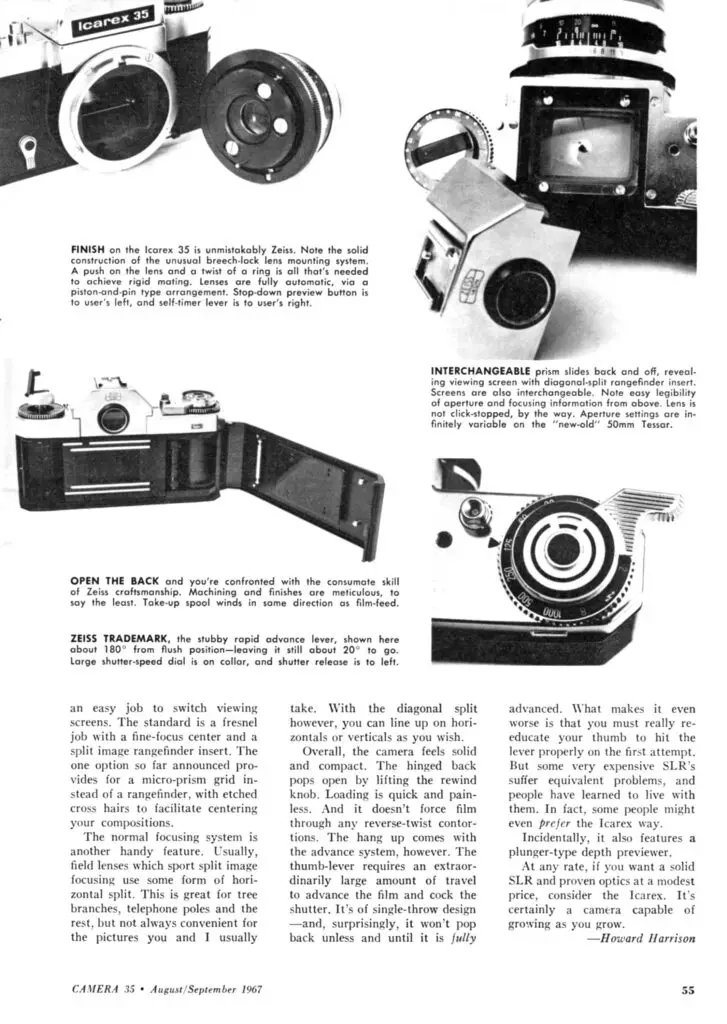

In the short two page preview above of the Icarex 35 from the August/September 1967 issue of Camera 35 magazine, the author starts out praising the camera’s build quality and lens mount. Highlights of the camera were it’s tried and true fully-automatic 4-element Tessar lens, the interchangeable viewfinder, easy film loading, and standard focusing screen with diagonal split image.

Less impressive however was the stubby film advance lever, which the magazine chides for both it’s stubby length, but also that it requires a long throw and doesn’t support intermittent movements. Most concerning however was the all new lens mount, for which no third party lenses exist, and that it wasn’t even backwards compatible with Zeiss-Ikon’s own Contarex mount.

The inability for the Icarex to accept Contarex lenses was likely because the mount was already finished in the original Bessaflex prototype and would have delayed the release of the camera to adapt it, but more significantly that Contarex lenses did not have a diaphragm control on the lens itself, but rather were controlled by a wheel on the body. To adapt Contarex lenses for use on the Icarex would have required either a complete redesign of the camera or some kind of complicated and expensive adapter. So while Zeiss-Ikon made the smart (and economical) decision not to support Contarex lenses, it was still a point of contention for some early adopters.

Initially, the Icarex 35 was sold with the pentaprism viewfinder as standard, with an optional waist level finder available for an additional $12 (dealer price). Whether the camera was equipped with the prism or the waist level finder, it was still called the Icarex 35, however by 1968 a new metered prism was available which on the face of the prism was labeled Icarex 35 CS. The inclusion of the “CS” suffix was consistent with the earlier Voigtländer Ultramatic CS which also had a metered prism. Owners of the original Icarex 35 could buy the metered prism by itself for $62.95 (dealer price) or with the camera. When sold with the camera, the entire outfit was called the Icarex 35 CS. While researching this article, I could not find any difference between original Icarex 35 bodies and those sold as the Icarex 35 CS. Other than the prism, I do not believe there were any differences between the two.

One interesting change which occurred with the release of the metered prism was Zeiss-Ikon’s inclusion of the Voigtänder name on the prism itself. Although the body still only had the Zeiss-Ikon logo, the CS prism was labeled Zeiss-Ikon/Voigtländer, a detail that was shared on other cameras from the same era such as the Zeiss-Ikon Voigtländer Vitessa 1000SR.

In 1968, with the new metered prism came a second Icarex 35 model, called the Icarex 35 S. The “S” model included a coupled CdS exposure meter in a non removable prism. This necessitated an an entirely new top plate which had higher shoulders than the original model, but had the benefit that the meter was now coupled to the shutter speed. The depth of field preview button was still required to take an accurate reading, however the Depth of Field preview button had a lock which would allow you to keep it pressed in without having to maintain pressure on it.

According to a 1968 Zeiss-Ikon dealer catalog, prices for all available versions of the Icarex 35 series are as follows: (actual retail prices were typically less)

- Icarex 35 body only, no prism and no lens – $93

- Icarex 35 body w/ waist level prism – $105

- Icarex 35 body w/ standard prism – $125

- Above with 50mm f/2.8 Tessar – $169

- Icarex 35 CS body w/ metered prism – $155.95

- Above with 50mm f/2.8 Tessar – $199.95

- Icarex 35 S body only – $160.95 (1970 dealer price list)

In 1970, clearly feeling the pressure from even more Japanese SLRs and a general stagnation of the entire German camera industry, Zeiss-Ikon revised both the Icarex 35 and 35 S models offering them in both the original Icarex bayonet mount and also with the M42 “Universal Screw Mount”. Although a mount dating back to the 1940s, the M42 screw mount was still very popular with users of a huge number of German, Japanese, and Soviet camera systems. Both VEB Pentacon and KMZ in Russia were churning out millions of screw mount Praktica and Zenits, and in Japan, Asahi Pentax, Ricoh, Chinon, and several other makers were sticking with the venerable mount, meaning that there were a huge number of lenses available, increasing the potential number of customers who might take a chance at a screw mount Zeiss-Ikon SLR.

Fun Fact: In 1970, the West and East German Zeiss-Ikon companies agreed to share trademarks and as a result the Zeiss-Ikon logo changed. The new logo had a flat bottom compared to the curved from the original, and the line in between the words ‘Zeiss’ and ‘Ikon’ was flattened and no longer extended to the edges of the logo.

The Icarex series was unchanged other than getting the suffix BM for Bayonet Mount added to it’s name, and the new screw mount version being called the TM for Thread Mount. The BM and TM Icarex 35s were produced until at least 1971 when the company stopped making cameras.

All Icarex models were available in both black and chrome bodies, although chrome is the most common. A small number of cameras were sold with a “Pro” engraving on the front face of the camera, beneath the rewind knob. According to Larry Gubas, these Pro models were not mentioned in any Zeiss catalog and were only available in some US and French markets. Other than this engraving, the Pro cameras are no different than non-Pro cameras. Versions of both the fixed and interchangeable prism Icarexes exist with the Pro engraving, and they have been found in both black and chrome, although black was the most common.

Prior to 1970, it was clear that Zeiss-Ikon was struggling. Sales were stagnating, and as long time employees retired, the company was not replacing them. Despite what was clearly becoming the company’s demise, work on a new SLR commenced with a camera called the Zeiss-Ikon SL 706.

According to Larry Gubas’s book, “Zeiss and Photography”, development of the SL 706 was originally to be given the name Contaflex, but struggles within the company resulted in the camera being finished with materials on hand, and it’s working project code name SL 706 was used as it’s name. The camera was rushed to completion and a small number were offered up for sale.

This model, clearly based off the Icarex body was the “S” model with fixed prism with updated cosmetics, but adding support for open aperture metering. Despite having offered a metered Icarex since 1968, all models to this point required the lens to be manually stopped down before an accurate reading could be made. The SL 706 took an approach that had been used by other metered SLRs in supporting lenses with fully automatic apertures. The SL 706 only came with the M42 screw mount, but it is plausible that an update to the bayonet mount could have been made to support it too. A range of 4000 serial numbers were set aside for the SL 706, but it is not clear whether all were made. The true number is likely much less than that.

On August 4, 1971 all camera manufacturing at Zeiss-Ikon Stuttgart ceased, and every single model was effectively discontinued. In 1972, Zeiss-Ikon would liquidate many of it’s locations and factories, selling both the Voigtländer name, it’s trademarks, and the Braunschweig factory to Rollei-Werke Franke & Heidecke, makers of the long lived Rolleiflex TLR.

In a strange twist of fate, shortly after it’s acquisition of Voigtländer, Rollei would re-release the SL 706 as the Voigtländer VSL 1. The VSL 1 was unchanged from the SL 706 other than by name and was available in both chrome and black bodies. The first 500 or so examples were built in Germany at the Braunschweig factory, but production was later shifted to a factory in Singapore that Rollei owned and also built their highly successful Rollei 35 camera. Quality control of the Singapore made models is said to have been less than that of German models. A name variant of the VSL 1 exists called the Ifbaflex M102 and was made for a French distributor.

The Voigtländer VSL 1 was produced along side two other SLRs called the Rolleiflex SL35 and SL350, which were completely unrelated models that Rollei had been producing since 1970. The SL35 and SL350 used their own bayonet lens mounts and shared a similar feature set to the VSL 1. In 1976, Rollei would discontinue both their SL35 and SL350 models, and release a version of the VSL 1 with the SL35’s bayonet lens mount. This model was called the VSL 1 BM to differentiate it from the original VSL 1 models with the M42 screw (thread mount).

Finally, one last model called the Voigtländer VSL 2 automatic which upgraded the VSL 1 BM adding aperture priority automatic exposure. The camera was produced in small numbers and is very rare today. The Voigtländer VSL 2 automatic was the last iteration of the Icarex family, dating back to it’s own Bessaflex prototype dating to the early 1960s.

Additional Voigtländer models called the VSL 3-E, VSL 40, and VSL 43 also existed, but they are unrelated cameras, the last two of which were produced by Cosina in Japan.

Today, despite many decades passing since the era of their camera making dominance, Zeiss and Voigtländer are respected names in the camera industry. Carl Zeiss still makes lenses for present day film and digital cameras, and in 2000, the Voigtländer name was resurrected once again by Cosina in a lineup of Japanese made Voigtländer Bessa rangefinders. Several models exist, found with and without viewfinders, and using the Leica Thread Mount, Leica M-mount, and Contax mount.

The Icarex series of cameras aren’t the most popular for collectors, but they remain an excellent addition to any collection for their excellent build quality, modern design, and excellent lenses. While cameras like the Contarex will fetch far higher prices at auction, a good working Icarex body with lens is a special camera, both to shoot film in, and to sit on a shelf. If you have an opportunity to pick up one of these cameras at anything close to an affordable price, do yourself a favor and check it out!

My Thoughts

West German camera makers weren’t known for focal plane shutter SLRs throughout most of the 20th century. Sure, Wirgin produced a long line of excellent Edixa SLRs with a cloth focal plane, but apart from them, nearly every other West German SLR by AGFA, Kodak AG, Voigtländer, and Zeiss-Ikon used some type of Compur or Prontor leaf shutter.

That all changed in 1960 with the release of the Zeiss-Ikon Contarex. The Contarex was an insanely complicated and expensive camera that took the German tradition of “if something could be built with 10 parts, the Germans would use 20” to the next level. Although the camera performed well and had some of the best lenses available for any camera system at the time, the camera’s exclusivity meant that few ever had a chance to use one. That exclusivity still exists today as working used copies of the Contarex with a lens can sometimes reach upwards of $500 or more. I was lucky enough to have one of my own that I picked up for far less than that, but if you were into West German cameras in the 1960s (or today) and want to shoot something a little more affordable, the Voigtländer designed but Zeiss-Ikon labeled Icarex was the best option you had.

While the Icarex might not live up to the Conatrex’s heft or build quality, it is still a very stout camera. At 990 grams including the 50mm f/2.8 Tessar, it outweighs a Nikkormat FTN with a Nikkor 50mm f/2 which tips the scales at “only” 952 grams. The camera is almost entirely made of very shiny metal, with very little use of plastic, and exudes quality while holding it. Also unlike the Contarex which has a rather unorthodox control layout, the Icarex feels more like a modern camera, with controls located exactly where you’d expect them to be on most Japanese SLRs of the era.

Starting with the top plate, on the left is the rewind knob with fold out handle, which sits above a film speed reminder dial with both ASA and DIN film speeds. The dial is not coupled to the prism mounted meter, making it a tad redundant on this model. Above and to the right of the film reminder is a small release button for the interchangeable prism.

To remove the prism, press and hold this button while sliding the prism towards the rear of the camera. I have always preferred read sliding prisms like ones on Miranda and Topcon SLRs over the kind you have to lift up on like in the Nikon F-series and Exakta cameras. Although the Icarex body is fully mechanical, the CS meter requires a battery to work. A swing out battery holder near the front of the underside of the prism is where a PX625 mercury battery goes.

This being the CS model, the only real difference is that the included pentaprism contains an uncoupled Cadmium Sulfide exposure meter with match needle capability. That the meter is uncoupled is unfortunate as by 1968 when this camera was sold, most metered SLRs had meters that were in some way coupled either to the shutter speed dial, the aperture ring on the lens, or both.

Since it is uncoupled, the meter has no way of knowing what f/stop is selected on the lens, so you must press the depth of field preview button near the bottom of the lens mount each time you want to take a reading. Before you do that however, you must set both the film speed and shutter speed dials atop the prism to whatever film is loaded and what shutter speed you wish to shoot with. Scales exist for both ASA film speeds from 25 to 1600 and DIN speeds from 15 to 33. Assuming you have everything correct, point the camera at your subject, press and hold the depth of field preview button and looking through the viewfinder, look for the match needle. If the reading is either too high or too low, you must either select a different shutter speed or f/stop until everything lines up. This is a slow and tedious process that in my opinion, is no better than just using a handheld meter, but hey, at least Zeiss-Ikon could say they had a metered Icarex.

To the right of the prism, is the cable threaded shutter release button, with a small shutter readiness indicator below and to the left of it. When this indicator is white, the shutter is cocked and ready to go, when it is black, the shutter is uncocked. Dominating the right side of the top plate is the combined film advance lever which sits above the shutter speed dial, and below a film type reminder dial.

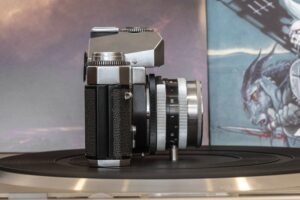

The shutter speed dial is a bit strange on this camera as it is a flat wheel which rotates between shutter speeds from 1/2 to 1/1000 plus Bulb and a dedicated X-sync setting. The dial can be spun directly from Bulb to 1000 without having to go the complete opposite direction. A nice thing about the shutter speed dial is that it reaches the front edge of the camera, allowing you to rotate it with your right index finger by sliding it from left to right. In addition to the unusual shutter speed dial, the film advance lever is very stubby. The total movement of the lever is about 220 degrees and must be completed in it’s entirety before firing the shutter. Shorter, partial movements are not allowed.

Flip the camera over and on the bottom is a centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket, the rewind release button, an engraving reminding you that the camera was made in Germany and that’s all. On the base of the mirror box beneath the shutter is a little metal post which helps the camera sit level on a flat surface, but other than that, there is nothing else to see.

One cosmetic change that was made to the Icarex from the original Voigtländer Bessaflex are the angled edges of the body. Where the prototype had Leica-like curves, the Icarex has Canon rangefinder-like angles. The only things to see on the camera’s sides are the chrome metal strap lugs which are on the angled facet facing forward. Having them face foreword like this helps to prevent the camera from tilted forward when dangling from your neck. Seen from the left side of the camera on the side of the mirror box are the PC ports for both F and X flash sync.

The rear of the camera has a large swath of body covering across the entire door. Above it is the rectangular eyepiece for the viewfinder, surrounded by a round black ring which looks to be threaded for viewfinder accessories. Interestingly, above the eyepiece is a logo that has both Zeiss-Ikon and Voigtländer logos. This location is the only part of the camera that hints at the camera’s Voigtländer roots. The metered CS model came out two years after the original and it is interesting to note that the original Icarexes do not mention Voigtländer at all. To the left of the eyepiece, below the film advance lever is the automatic resetting exposure counter.

Lifting up on the rewind crank and giving it a tug releases the right hinged film compartment door. Despite the professional level build quality of the Icarex, the door is not removable, eliminating any option for interchangeable backs. Film transports from left to right onto a single slotted and fixed take up spool. The take up spool is one of the few plastic parts of the camera, but the rest of the film compartment is all metal. An interesting ribbed pattern flanks the film gate on the back of the mirror box, and brightly polished film rails are above and below it. The inside of the door has a large black metal painted film pressure plate, and do the side a metal roller which helps maintain flatness as film transports through the camera. Unlike most SLRs from it’s era, the Icarex does not use foam light seals. A fabric seal is along the hinge, but the upper and lower door channels do not need any.

One of the very few ergonomic failures of the Icarex 35 CS is that when looking down upon the top of the lens, the large metered prism overhangs about half the lens, completely covering the aperture ring. In the image to the right, I removed the prism to be able to see it.

Looking down upon the top of the lens, the aperture ring is closest to the body with aperture f/stops from 2.8 to 16 available. The aperture ring does not have click stops and turns extremely smoothly, allowing for infinitely variable diaphragm control. The ring is made of chromed metal with a strong knurl, giving it excellent tactile feel and grip. Near the front of the lens is the focus ring, which like the aperture ring is also made of luxurious chromed metal. This ring is also extremely smooth and has a range of 18 inches (0.45 meters) to infinity. Between the aperture and chrome rings is a white painted depth of field scale.

Up front, the lens uses a breech lock bayonet, very similar to Canon’s R/FL/FD mount in which a black painted metal ring closest to the body rotates to unlock the breech at which point you lift the lens off the body. The difference with a breech lock bayonet compared to a regular bayonet is that at no point does the lens mount ever rotate against the lens. This, in theory, means that there is no chance that the mating surface of both the lens or the body could ever get worn down, affecting the flange focal distance. In reality, this is unlikely to happen, as most SLR makers settled on a traditional bayonet mount with no ill effects. In my early years of collecting, I strongly disliked breech lock lenses, but I’ve grown to no longer have a strong opinion. I don’t think they’re better or worse, just different.

Also on the front of the camera near the 8 o’clock position around the lens is the mechanical self-timer. The self-timer on the Icarex is unusual as there is no way to stop it. I found that by rotating it to the extent of it’s travel, it would always immediately start counting down. This happens with or without the shutter being cocked. Thinking that perhaps the one on my CS was not working, I dug out a second non-CS Icarex 35 I had, and that one worked the same way too. Upon reading the original user’s manual, it turns out this is by design. To use the self-timer, you first cock the shutter, then rotate the self-timer lever as far as it will go, and then at the end of it’s travel, let go, and an approximate 8 second countdown begins. There is no way to set the self-timer and then walk away leaving it set for later.

Finally, near the 5 o’clock position around the lens is the depth of field preview plunger. This plunger must be used to take an accurate meter reading using the prism mounted meter as the meter is not coupled to the lens, so it has no idea which f/stop you have selected. On the Icarex 35 CS, this plunger is momentary and must be held for as long as you need the lens to remain stopped down. On the fixed viewfinder S versions, the plunger has a lock which can keep the lens stopped down.

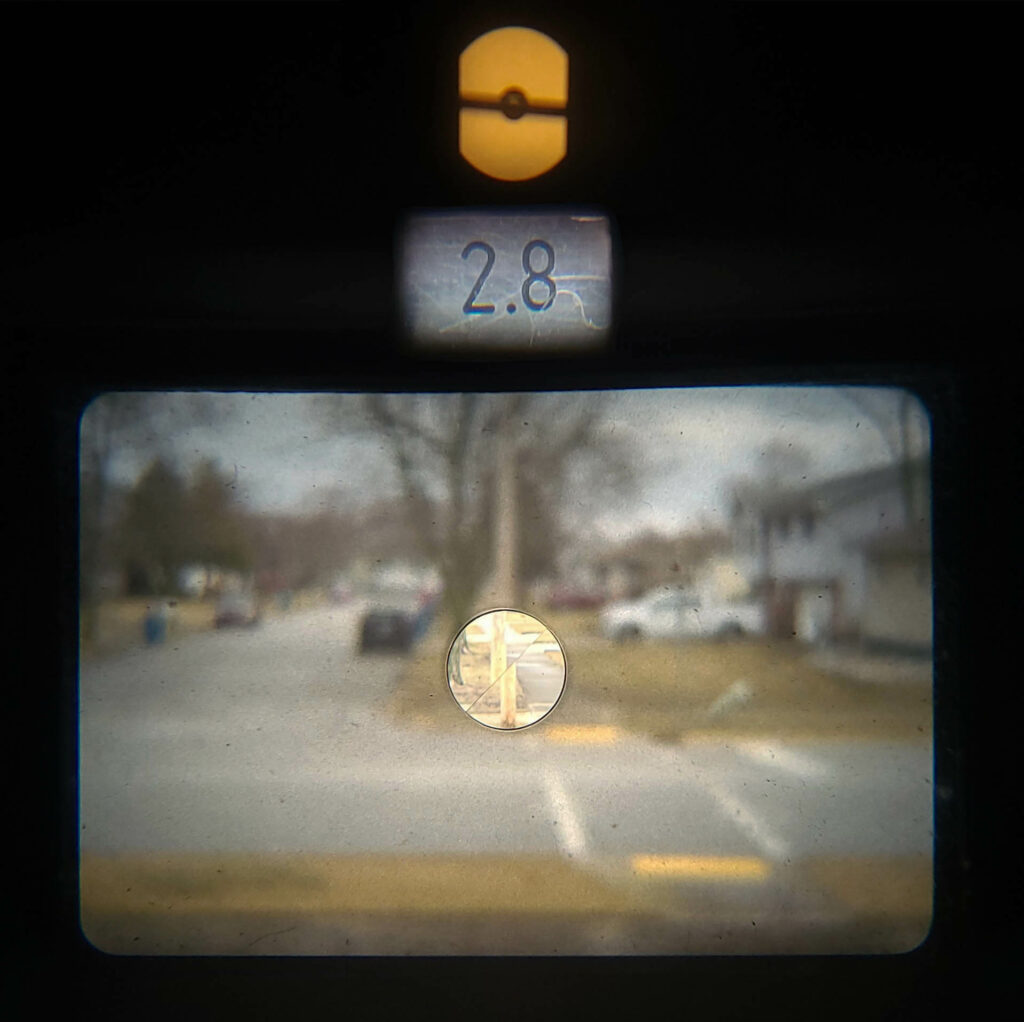

The viewfinder is bright and very modern. Brightness is very good corner to corner and compares favorably to the best SLRs of the late 1960s and only barely falls short of later SLRs like the Minolta XD-11 or Nikon F3. Although the focusing screens are interchangeable, the one that came on this one has a split image focus aide in the center in which the split image is at a 45 degree angle. This is different from most where the split is horizontal as it allows you to use both vertical and horizontal lines to focus on. In the gallery below, I have images of the lens in and out of focus, which helps you see the split image easier. Around the split image is the ground glass. There is no visible Fresnel pattern, so I am unsure of what technology is used to make it so bright, but it is very good.

Wearing prescription glasses, I can see all four edges of the viewfinder, however above the viewfinder is a rectangular Judas window for reading the selected f/stop directly from the top of the lens, and above that is a reflected match needle from the prism mounted exposure meter. It was impossible for me to see the entire focusing screen, aperture display and the exposure meter needle at the same time. In the gallery above, I did a composite shot showing them all at once, but I could not see it this way. If I remove my glasses and press my face as close to the camera as I can, the aperture window and meter barely come into view, but it is difficult to see all three things at the same time.

The Icarex 35 CS is an impressive camera. Even more impressive is that it was based off a discontinued prototype developed by Voigtländer and later re-released by Zeiss-Ikon. Usually when one company resumes a design from an earlier company, the results can be mixed, but overall the Icarex is a pretty good camera. It’s certainly not perfect, as seeing everything in the viewfinder is difficult, the prism overlaps the top of the lens, and the usefulness of the uncoupled meter is debatable. But overall, Zeiss-Ikon’s typical quality and their excellent lenses more than definitely make up for the camera’s few shortcomings. But what kinds of images does it make? Keep reading…

My Results

The Icarex 35 CS used in this review is actually the second one I had. The first had a good body and shutter, but the lens was damaged and the iris would not stop down. Sadly, I did not notice this until after shooting my first roll, which resulted in an entire roll of grossly overexposed images which I could not use.

It would take me a little bit of time before I could find another lens, but when I did, I took it with me to Northern Michigan in the spring of 2022. I would shoot the camera a second time in the summer of that same year, this time with some semi-expired Kodak BW400CN.

If you’ve read enough of my reviews, you might have noticed a pattern when I get to this point in the review where I need to talk about the images I got from whatever it is I’m reviewing. This pattern is likely more evident when whatever camera it is has a well regarded lens by a known manufacturer. In the case of the Icarex, we’re talking about a camera with a Tessar lens. In this case, it is a West German Carl Zeiss 50mm f/2.8 Tessar. Of all the Tessars, it is commonly believed that the West German Tessars are of higher quality than their East German Jena counterparts, but really, they’re all good.

The Tessar is one of the longest surviving lens formulas as it was invented by Paul Rudolph in 1902 and is still in use today. Countless Tessars have been built over the past 120+ years by Zeiss and copies were made by everyone from Bausch & Lomb to Nippon Kogaku to KMZ. It is arguably, the most successful lens formula ever made.

So yeah, the images are going to look good. I’ve said it time and time again. When I looked at the images on my computer screen after scanning them in, I was pleased with how they look, but in an effort not to completely repeat myself in this section, I’ll contradict something I’ve said when talking about lenses, in that it doesn’t matter what camera you have it on, you’re going to get great images. And while that’s still mostly true, I’ll concede that while the lens has the greatest influence on technical image quality, if mounted to a miserable camera that is difficult, or otherwise sucks to use, you likely won’t be inspired to make great images with it.

So that brings me to the Icarex. Yeah, the lens is sharp corner to corner with excellent contrast, accurate colors, just the right amount of vignetting in the corners so as to give it a film-like aesthetic without feeling sterile. But on this specific camera, I do believe that the camera added to my enjoyment which shows in the images I got from it. When I first picked up the Icarex, I immediately felt it’s high quality, appreciated it’s shiny chrome, all metal controls, and tight tolerances.

But while using the camera, the entire experience somehow felt elevated compared to just another mechanical 35mm SLR from the 1960s. The Japanese were well known for good quality too, and their more efficient methods of mass production quickly eroded the influence of the entire German camera industry, but even by 1968 when Nikon and Canon SLRs were hot commodities, the Germans proved that they still had something the Japanese didn’t. I can’t exactly describe it, and it won’t make sense until you shoot one for yourself, but the Icarex has that extra +1 that prestige brands like Mercedes and BMW have over other auto manufacturers, why after 170+ years, A. Lange & Söhne watches still appeal to those who can afford them, and why Hugo Boss still ranks highly among luxury fashion brands.

The Icarex 35 CS doesn’t do anything that a Nikon F or Topcon SLR can do, it uses the same film, and it accepts some of the same lenses that are available on a huge number of other brands, but it all adds up to a luxury experience that you need to experience to understand. I always felt like I had a precision instrument that I needed to be more purposeful and calculated in my use. I believe that this elevated my photos and allowed me to get better results than I might have otherwise gotten with something else.

Now, before I lose any additional readers as they all vomit from my over the top adulation of what is essentially a pretty standard late 1960s SLR, I’ll admit there’s a few things about the Icarex which aren’t ideal. For starters, the implementation of the meter really sucks. Having a prism mounted meter isn’t unusual as the Nikon F of the same era worked the same way, at least the Nikon couples both to the lens and shutter speed dial, whereas the Icarex is completely uncoupled to both. This means that you can only take a reading by stopping down the lens, therefore darkening the viewfinder before you can take a reading. But even then, you still need to manually duplicate the appropriate shutter speed on a separate dial on the meter itself and on the body.

If this isn’t bad enough, the location of the match needle within the viewfinder is WAY above the focusing screen. While wearing prescription glasses, you cannot see the meter without completely repositioning your eye, looking far above your image. Even without glasses, I would suspect most people had to keep moving their eye around. It adds up to a very slow process that I suspect resulted in a lot of users reverting back to a hand held meter. For me, I just ignored it altogether and shot my rolls using Sunny 16.

Ergonomically, the film advance lever is stubby, which isn’t much of a problem itself, except that it requires quite a long throw to advance the film to the next exposure. An entire motion goes well past 180 degrees, to probably somewhere around 220 degrees. In addition, the motion must be done in one complete motion. You could minimize the effort of a long throw by allowing several smaller motions, but the Icarex doesn’t allow for that.

Finally, a very minor nitpick is the location of the shutter speed dial beneath the film advance lever is a bit strange. The selected shutter speed is tightly positioned near the shutter release, which despite being able to see the entire ring under the circle, just feels a little odd that this is where the designers decided to put the index mark.

The good news is, just ignore the meter (or use an unmetered Icarex) and just get used to the location of the shutter speed dial and how the film advance works, and the rest of the camera is a pleasure to use. The West German Carl Zeiss lens has all metal touch points, the chrome is thick and shiny, the camera does not creak in your hands, the lens mount is firm, and all of the camera’s tactile controls feel like they could take anything you throw at them.

So there you have it. It is clear that quality was still a priority in Germany when this camera was made giving it a unique feel compared to those made in other countries. West German lenses were still the best money could buy and that despite “only” having 4 elements and “only” opening up to f/2.8, the images you’ll get from it are as good as any out there. The Zeiss-Ikon Icarex 35 CS is not perfect, the meter isn’t very useful, and there’s some ergonomics missteps, but what’s good about the camera far outweighs what isn’t. If your collection consists of nothing more than Japanese SLRs, leaf shutter SLRs, or Exaktas and you have yet to experience what West Germany was doing with 35mm SLRs, any Icarex is worthy of adding to your collection. Don’t feel bad if you don’t have the top of the line lenses, as any will do! Highly recommended!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Icarex

https://www.pacificrimcamera.com/pp/ziicarex35.htm

http://www.earlyphotography.co.uk/site/entry_C709.html

https://thegashaus.com/2021/01/11/zeiss-ikon-voigtlander-icarex-35s-tm-pro/

http://oldgoodlight.blogspot.com/2021/02/icarex-35cs.html

https://vintage-photo.nl/icarex-35-the-marriage-of-zeiss-and-voigtlander/

http://www.klassik-cameras.de/Icarex.html (in German)

Great review- as usual. I’ve long admired these, but never owned one!

Thanks Kurt! You really should check one out. I could see you liking it. I only have the 2.8 Tessar, but there is an f/2 Ultron lens that they made for it too. Novak has an example of one.

Quid des Rolleiflex 35M et 35ME ?

Mike, it seems to me that the metering procedure in the Icarex is the same as the metering procedure in a Pentax Spotmatic, or in a Canon FT (I have both of these). In all three, you first operate a switch of some sort to close the diaphragm to the set working aperture. You then adjust either the aperture or the shutter until a needle in the finder matches a mark indicating correct exposure.

But this is not an “uncoupled meter”. To the contrary, in all three the meter readout in the camera (needle) reacts to changes made on the aperture ring, the shutter speed dial or the ISO dial.

The correct description would be that these cameras rely on “stop-down metering”. It is true, of course, that stop-down metering is more cumbersome than open aperture metering, but that does not make it “uncoupled”.

Uncoupled meters are lot more cumbersome. Changes set on the aperture ring or shutter dial have no effect on the meter readout, and the user must read the meter and then transfer indicated values to the aperture or shutter controls.

The meter on the CS is definitely uncoupled. When you remove the prism, there is absolutely no physical connection to the body. I explain in the article that you must first set the shutter speed on the meter to match what the body is to take a reading. You are thinking of the Icarex 35 S which has a built in coupled meter, and does not have an interchangeable prism.

I cover all of this in the review! 🙂

Mike: you are right of course—I think I overlooked the sentence about duplicating the shutter speed settings on the meter and the body. To me though, the meter implementation does not seem that bad. Unless I missed something else, it looks like once film speed is set (on the meter obviously), and the shutter speed settings on the meter and body are matched up, the user can then set the correct meter-indicated aperture without leaving the viewfinder, because the finder includes a meter needle read out, as well as an aperture readout. In fact, this seems better than my Canon A-1, AE-1 or T-70 cameras, which, when you leave the auto exposure modes, require manually transferring a value from the meter readout to the body or lens!

Thanks a lot for your wonderful blog! I discovered it just a couple of weeks ago but it has already given me lots of pleasure.

An Icarex was my first quality SLR. That was the fixed viewfinder prism model 35S which I bought in 1971 (I think). My father then already owned a model 35CS which I later inherited. My 35S had a Tessar 50/2.8 lens. My father’s camera had the Ultron 50/1.8 (not f:2).

I totally agree with Geert DePrest about the metering. I have used this camera quite a lot. My metering procedure goes like this: Press the stop down plunger with your left thumb and hold it in while adjusting the aperture with the left index finger until the needle is on the mark. Release the plunger and you are ready for exposure. I wasn’t bothered by the darkening of the viewfinder while metering as I would never try to focus at the same time as taking a meter reading. The operation was speeded up by the lack of click stops on the very smooth aperture ring. The meter needle is a bit slow in it’s response and shows the well-known memory effect of the CDS cell. I could speed up the metering process by closing the aperture a bit too much and opening it again until the needle just matched. I really didn’t find this any slower than the open aperture metering in my wife’s Olympus OM1 and being able to observe the chosen aperture through the judas window was really great. But I must admit that it is easy to forget to match the meters shutter setting with the camera’s setting.

If I am not mistaken the meter circuit of the Icarex is bridge coupled and therefore not dependent on the exact battery voltage. It will work perfectly fine with a 1.5V LR625 battery.

Bu the way: A similar type of uncoupled meter prism was offered for Exakta by a couple of independent west German companies. Miranda also had at least one model with the same system.

As far as I know the Icarex Tessar isn’t really a Tessar but a rebranded Voigtländer Color Skopar developed by the famous lens designer Wilhelm Albrecht Tronnier who also was the man behind the Ultron lens. It is said to be sharper than the Carl Zeiss Tessar and I believe it’s true. At any rate it is an excellent lens. I have both the 35mm f:3.4 Skoparex and the 135mm f:4 Super Dynarex in Icarex mount. Very sharp lenses. The Ultron f:1.8 is in a class by itself when it comes to sharpness, but also plagued by flare. I think the Tessar is a better choice. I also own a Color Ultron from a Voigtländer VSL 1 (M42 mount). That lens is multicoated and perhaps my best SLR lens. It doesn’t exhibit the concave front element of the Icarex Ultron.

My experience is that the fixed viewfinder Icarex 35S is not a reliable camera. I had both my Icarex cameras serviced by a Zeiss-trained repair man who supported this view. Zeiss Ikon Voigtländer didn’t manage to get things right when they integrated the meter into the camera body.

A last comment: The take up spool in the Icarex winds the film in the same direction as it is in the cassette. Much appreciated when it comes to threading the film into a plastic reel for developing as it doesn’t get a backwards curl!

My parents moved me to a medium level city when I was a wee lad, and the history of that city was mostly German. When I was in high school, 68-72, the local pro shop had a lot of old “Duetschers” working there, and a pretty decent supply of current German cameras, like Leicas, Rolleis, and this, as well as the Contarex Electronic. Sure there were a lot of Japanese stuff in the display cases, but those old timers really loved their German lenses. I managed to snag a bunch of deluxe printed brochures on these, which used to wow me in study hall! Alas, far too expensive for me new, but later on, I bought a new Praktica Super TL, and altho is was a pretty loose and rough camera body, the lenses on it certainly held their own to my friends Japanese cameras. When I held the Icarex, and Contarex, in the camera store, they just exuded quality.

Great story, Andy! Thanks for sharing. I’ll admit to being a little jealous that I never got to experience camera stores during film’s heyday.